Fretboard Harmony 1

By Peter Altmeier-Mort

In the performance and study of music, the player, the music, and the instrument, are the components of a whole whose engine (and source of energy) is really the person themselves, PLUS their perception and understanding of what is being played – particularly its form and structure.

Share this:

[feather_share]

INTRODUCTION:

As two points of comparison, one could propose that a professional racing car driver could not afford to be ignorant of the structure and way in which the engine of his vehicle works. He would no doubt feel less able about his role nor NOT knowing all about it, and consequently perform only up to the limitations that this might impose. In the performance and study of music, the player, the music, and the instrument, are the components of a whole whose engine (and source of energy) is really the person themselves, PLUS their perception and understanding of what is being played – particularly its form and structure.

Fretboard harmony is a tool to be applied in achieving these ends so far as the harmony of guitar music, its positioning on the instrument, and it’s not inconsiderable peculiarities are concerned. The study of harmony and its application to the instrument being played, is simply part of becoming musically literate. It is a fundamental skill that helps a musician perceive what a composer has done to create the effect that so pleases the player and the audience (if there is one), as the music unfolds its communication. Harmony, as well as melody and rhythm, is always a part of the composer’s communication apart from the whole area of his intended emotion, style and interpretation. Like everything else in music, harmony has to be “heard” before one can do anything with it emotionally.

Equally important is the fact that understanding the music’s harmony is an aid to memorisation of a piece, and, understanding the options on the fretboard gives the player greater freedom for a variety of left hand fingerings. In many students a large amount of “muscle memory” is enforced upon the act of memorising a piece of music – a time consuming pursuit in itself. Under the pressure of performance (public, private or in exams for example) the “muscle memory” approach to memorisation is liable to complete collapse, mainly because by its nature it is robotic. When this memory “system” falters the performer quite often has no other reference point from which to pick up from – no amount of “muscle memory” will cover for a lack of understanding of the music. The former is actually a symptom of the latter and unfortunately both understanding, or a lack of it, are equally transmitted to the listener. This is not to say that the player must be consciously saying to him/herself “and now I am moving from a 1st inversion F major chord to a root position A minor chord” when performing a work. This amount of attention on the structure or harmony would be obviously detrimental to one’s freedom of expression and personal message in the music being played. But if, after the notes, rhythm and fingerings are established a piece IS then studied like this, even with limited knowledge an awareness of the music’s structure become inbuilt. It becomes an internal path the player follows within themselves as the music is played, never too far in the background of his/her mind and always available as a passing reference point for memorisation during the act of formally presenting music. This study or practice habit can even continue right on up into the refinement stages of preparing a piece – the moment of performance is the time to drop all this attention into the background and just PLAY.

DEFINITIONS:

Harmony – from the Latin/Greek roots “harmonia” meaning to join, fit together, which gives rise to the normal English use of the word as in agreement, understanding, goodwill or peaceful relations. In music, harmony is the fitting or joining together of sounds to form chords. More fully, it is the structure, function and relationships of chords.

Chord – a combination of 3 or more notes sounded simultaneously. In this text, the simultaneous playing of 2 notes any distance apart, is referred to as an interval. The concept of harmony concerning intervals occurs in that the 2 notes may sound harmonious or well fitting together, and following on from this, a pair of notes sounded together can often imply the sound of a 3rd note and therefore a chord. Some guitar tutors refer to intervals as chords, but it is probably best to maintain a distinction between the two, because it is the way in which intervals resolve or move one pair to another, that affects the way chords resolve or move one to another.

In music, the scale functions as a reserve of notes from which melody and harmony are formed. A piece is said to be “in the key of C major” because its melody and harmony (or chordal accompaniment) have been so constructed from the C scale. It is a scale that provides this type of order and organisation for the music. The character of a piece of music, to a large extent, is a result of the character of the scale that has been used. This explains the main difference in character between a piece in a major key and one written in a minor key – to begin with the character of the scales used is different, the major scale creating one emotional effect, and the minor another.

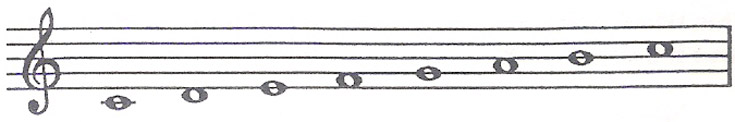

Our Western system of harmony or chords is based upon intervals of thirds (taken from within a chosen scale) placed one upon the other.

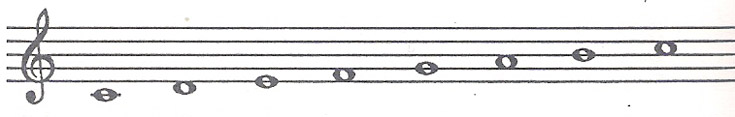

For example, consider the C major scale.

To build the chord of C, take the note C as the starting point and select from the scale an interval of a 3rd above this note. That will add the note E to the C.

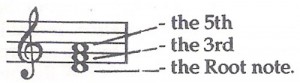

Now select from the scale the next interval of a 3rd above this E. That will add the note G, giving a complete 3 note chord of C major (remember the scale being used is C major) These notes are termed:

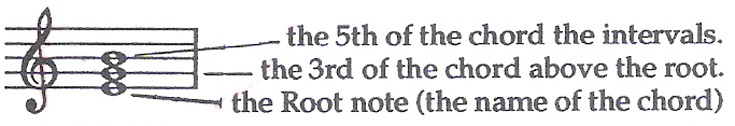

These 3 notes, C,E,G form what is known as the basic TRIAD of the C major chord. Triad – a group of three of something. The beginner will have seen this chord written several ways.

For now, it should be understood that any of these three different notes making up the triad, can be repositioned higher or lower on the staff, and that any of these three notes may be repeated in any single writing of the chord – whatever happens with the positioning of the notes, there is nothing else here but the basic C major chord. WHY they are rearranged is covered in the next section.

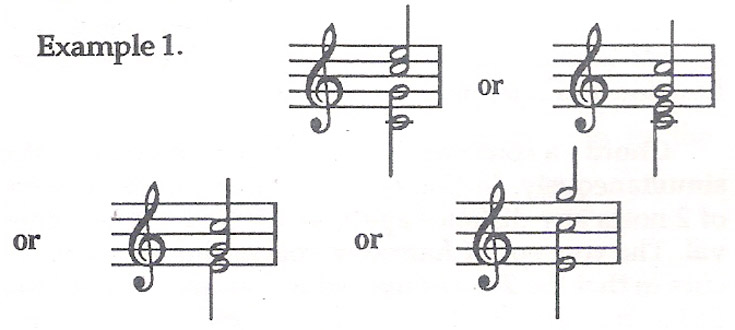

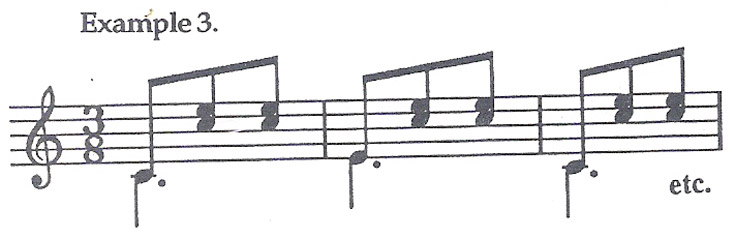

The beginner will also have seen the notes of a triad used in this musical context.

Looking closely at the notes employed here, it breaks down to being nothing else but a useage of the three notes of the C major triad C,E,G. The three notes of the triad are not played simultaneously as a chord would be, since the composer has designed here an arpeggio technique (from the Italian “arpeggiare” – to play like a harp) to be played over the notes within this triad. For now, such an awareness of the harmony and it’s use in this bar is a sufficient expression of it.

Neither do the three different notes forming a triad ALL have to be present in a statement of a chord. Beginners will be familiar with this musical context.

Here there are three notes used in each bar, but ALL three notes of the C major triad are NOT used in any one bar. The first bar has used only two C’s and an E, the second using two E’s and a C. Again, the harmony of each is nothing else but a “broken” formation of the C major chord, with the note G omitted.

Among themselves, musicians tend to use the terms “triad” and “chord” as interchangeable terms – which is fine if these terms of reference are agreed upon. To perhaps place some clarity on this for the beginner, “triad” simply describes those three different, fundamental notes of a chord (C,E,G as in the above examples) – it does not infer how they could be played, or how they may be written in music. As first defined, the term “chord” means three or more notes sounded together, and not ALL the three essential notes of the triad need to be present, but they usually are. Another use of this term is for those situations using arpeggios. An arpeggio is a “broken” chord – that is, the notes of the triad are broken up and sounded one after another in some deliberately constructed pattern. See ex. 2 again. So here, “chord” is used in analysis to describe the harmony of any given arpeggio, and thus the term IS applied to occasions when notes are in fact NOT being sounded together.

Returning to the C scale, build a triad now upon the second note of the scale, D again using intervals of thirds from the scale.

Example 4.

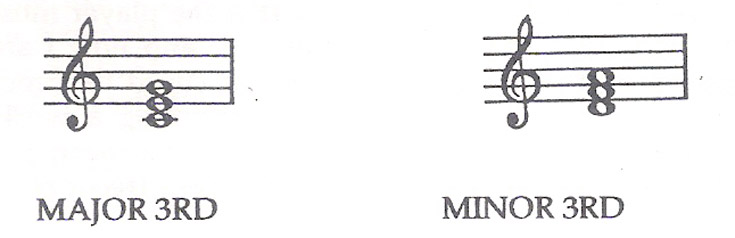

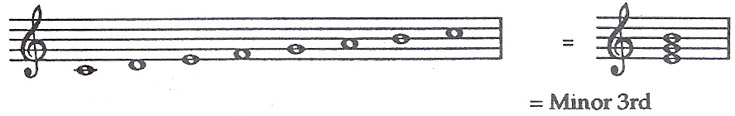

Now place this new chord beside the C major triad and observe the intervals between the Root and the 3rd of each chord.

It is the interval from a root note to it’s a 3rd, that determines whether the chord is MAJOR or MINOR.

The interval of a MAJOR 3RD is a distance of 2 tones from note to note (the C to E here). The interval of a MINOR 3RD is a distance of 1 ½ tones from note to note (the D to F here). Thus the triad built on the 2nd note or degree of a scale, in this case D is a MINOR triad – so this is the chord of D minor. Again, no matter how the notes of the triad (the root, the 3rd and the 5th) are distributed or positioned over the staff, the harmony used is still the basic D minor chord.

Returning to the C major scale, build a triad upon the third degree of the scale E, using intervals of thirds from this scale.

Example 5 –

Looking at this triad on the note E, it can be seen that the interval from this root note to its 3rd above (the note G) is again a MINOR 3RD. This is the chord of E minor.

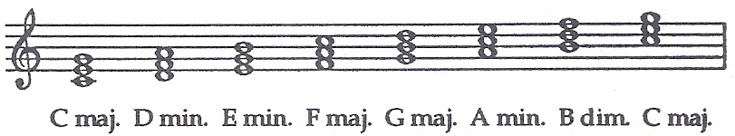

Consequently, the result of building triads on each note of the C scale is this:

Example 6 – min. B dim. C maj.

These are the chords and the harmony naturally occurring in the key of C major – the scale has provided it all. Any major scale will create the same sequence of major and minor cords, always with three major, three minor and one diminished. Observing the intervals between the notes of the triad built on the 7th scale note B, it will be seen these are minor 3rds all – this is the characteristic of the diminished chord, intervals of minor 3rds one upon another. To “diminish” or “make smaller”, is a direct reference to the interval of the 5th (from the B to the F) in this chord – it is semitone too small to be a perfect 5th. So this diminished interval places this name upon the chord.

A composer writing a melody in the key of C, would then choose from these chords his harmony for that tune. Any chords he chose NOT belonging to this group would amount to a “modulation” or change of key. Played as written, the above triads sound uninteresting on the guitar, but this presentation is the simplest form to explain the theory. The next section leads into a satisfying realisation of their sound and positioning on the fretboard.

Student exercise:

- On manuscript paper, write out the scales of G major, D major and F major without their respective key signatures. Place the correct accidentals (sharp or flat signs) into the writing of each scale – analyse and write in the correct names of all these chords. In particular, compare the chords of the key G to those of the key of C (as above).

- Draw the basic major, minor and diminished triads for EACH of these root notes – A, F and G. Use accidentals as necessary.

NEXT EDITION:

The VOICING of triads and how their notes are distributed through higher and lower positions on the staff.

Very informative and helpful for one who plays by ear (me) but who needs and wants to advance their playing and grasp of music theory. This makes the esoteric aspects of reading music more accessible.

Thankyou.