Get Smart with Jazz Guitar and Free Flowing Improvisation

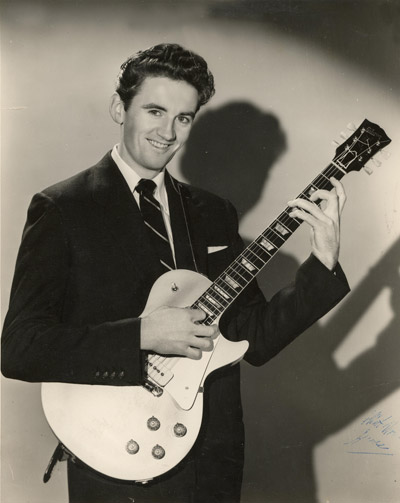

By Bruce Clarke

Musical learning should not be confined to the re-creation of what others have done” -an obvious enough statement, but one that is preached more often than it is practiced.

Learning should be an active process, not a passive one. At a certain point in each student’s development he must be encouraged to become involved in the actual creation of music with a no-nonsense, well-planned introduction to composition and/ or improvisation.

Share this:

[feather_share]

The student guitarist setting out to explore this dark world of his own musical potential will find that point of departure after he has acquired an understanding of (and some degree of control over) the diatonic system of major and minor scales, the harmonies they generate and the five scalar fingering-types he will use to unlock the web of tonal relationships that lie concealed across the fingerboard.

Even the humblest creative activity is valuable if it forces the student to think about the many ways he must learn to manipulate the available sound material – a central feature in functioning effectively as a musician. These creative beginnings also expose him to a unique, non-traditional type of intellectual “harmonic trial and error,” a sort of “musical mental arithmetic” we use to “come to grips with” and work out the syntax of our present day musical language.

So, in order to know yourself better through music, face up squarely to the gigantic challenge that lies ahead; to bring music’s sonic materials to heel.

Accept the fact that there is no way around this obstacle; there are no shortcuts to becoming musical.

Take stock of your current skills and activities.

• READING

• TONE PRODUCTION

• LEFT HAND DEXTERITY

• RIGHT HAND PICKING PATTERNS

• VIBRATO CONTROL

• DYNAMICS

• RHYTHMIC FEEL etc.

Are each of these falling into place?

Fine. As important as these are, they are no more the content of your musical education than chiselling is the full study of sculpture.

Yes, there it is – the ultimate challenge is content.

• WHAT DO I PLAY?

• WHERE DO I PLA Y IT?

• WHEN DO I PLA Y IT? and finally

• WHY DO I PLAY IT?

Did you notice that I gave equal status to both, composition and improvisation?

As the writer of a vast catalogue of diverse music, (scores for film, all areas of modern media, Jazz, contemporary and experimental forms and non-forms – a career spread over fifty years) and as an established jazz guitarist – I can state without fear of contradiction, that at the moment of conception, composition and improvisation are two sides of the same coin.

Each is the result of a creative spark “triggering off’ the imagination to respond to some musical problem or challenge, perhaps an assignment in progress. It may be the spontaneous reaction to musical or social pressures at play at some particular point in time. The imagination, in turn, draws upon the artist’s subconscious store of musical knowledge or accumulated creative experience.

The composer and improviser must develop the same fund of knowledge and creative skills – the main difference is that they shape their ideas in different time frames.

The composer works in a longer time frame; he may take days, weeks or even months to develop, rework and “hone-up” each parameter of his sonic design. We see, hear and (sometimes) marvel at the final product; we shall never see the contents of his wastepaper basket.

On the other hand, the improviser “lays it around our ears,” hot off the stove – second thoughts are not possible!

So, a crystallized rundown of the basic skills that these musical masters possess:

(1) An understanding of the full potential of their catalogue of available resources and

(2) The ability to apply the intellectual techniques we use to manipulate and reshape those resources.

Number one is the preparatory stage, and number two is what the nitty-gritty of improvisation is all about. It is useless to get involved with the latter problem until the concrete is firmly set in the basement.

So, let’s take a look at one of the more productive ways to fix stage one – into the mind and under the fingers.

It’s called, melodic continuity.

The pitch dimension of our “Diatonic System of Tonal Organisation” stands firmly supported by two legs: Scales and Arpeggios. Every aspect of our system’s key-based melodies can be analysed as:

Scales – small steps of tones or semitones (whole-steps, half steps)

or

Arpeggios – skips of a minor third or wider diatonic music holds or loses the listener’s interest according to how the composer or improvising artist controls the balance and flow of the ideas he fashions from these two sources.

Looking at the harmonic side of things, each chord in our system exudes a specific sound quality or musical colouration that must become firmly fixed in the mind if we are to fully explore the available tonal palette.

A METHODICAL APPROACH TO MELODIC CONTINUITY CAN SHOW US HOW TO RECOGNISE AND EXPLOIT THE INDIVIDUAL QUALITIES AND MELODIC POTENTIAL OF EACH PARTICULAR CHORD TYPE – SIMPLE AND UNADORNED, MODIFIED OR EXTENDED.

MELODIC CONTINUITY CAN FUNCTION AT MANY LEVELS:

• Whole – notes (1 to the bar)

• Half – notes (2 to the bar)

• Half – note triplets (3 to the bar)

• Quarter – notes (4 to the bar)

• Quarter – note triplets (6 to the bar)

• Eighth – notes (8 to the bar)

• Eighth – note triplets. (12 to the bar)

• Sixteenth – notes. (16 to the bar)

and each has something special to offer.

Mastery of the faster-moving groups (8, 12 and 16) will open the door upon high-speed decision making with regards to line shaping and balanced phrasing. They also help to unlock the many mysteries of the fingerboard which must be wiped away before we can expect to solo effectively.

But, in many ways the slower groups (1, 2 and 4) are the most challenging “ear-wise,” because greater care must be taken in the area of note selection.

Each note chosen must spell out the underlying harmonic quality.

There are a number of ways you might approach the job.

(a) Take a simple progression from the mainstream jazz repertoire: – perhaps All of Me, Autumn Leaves or Out of Nowhere could be a good place to start. Pre-record the changes, then write out and shape your melodic continuity ideas. Finally practice with the recorded track, and when ready, record. Listen carefully to the finished product many times, decide how it can be improved, then start all over again.

(b) A more advanced player might choose to work over some of the many professionally produced practice records that are available today.

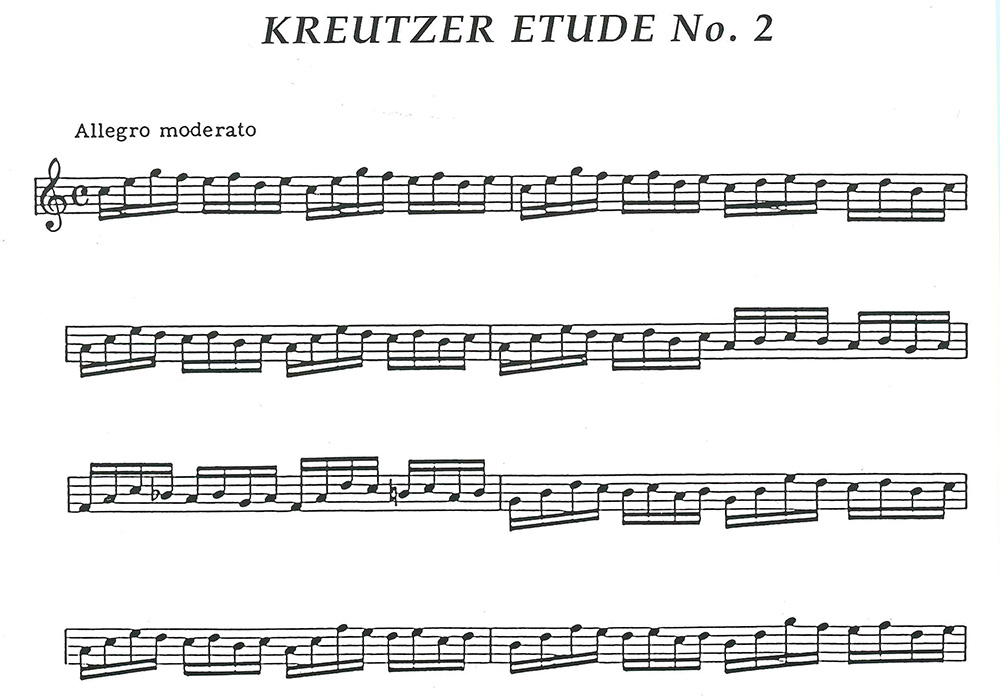

This form of practice is not unique to Jazz. The instrumental training procedures of European “classical” music abound with discipline studies based on continuous streams of equal notes, half-note studies, quarter-note studies, eighths, triplets and sixteenth-note studies which must be worked on daily.

Here’s one from a famous set of violin studies that works well on the guitar. Work out an acceptable fingering plan, then write the harmonic plan (the chords) that underlie the study.

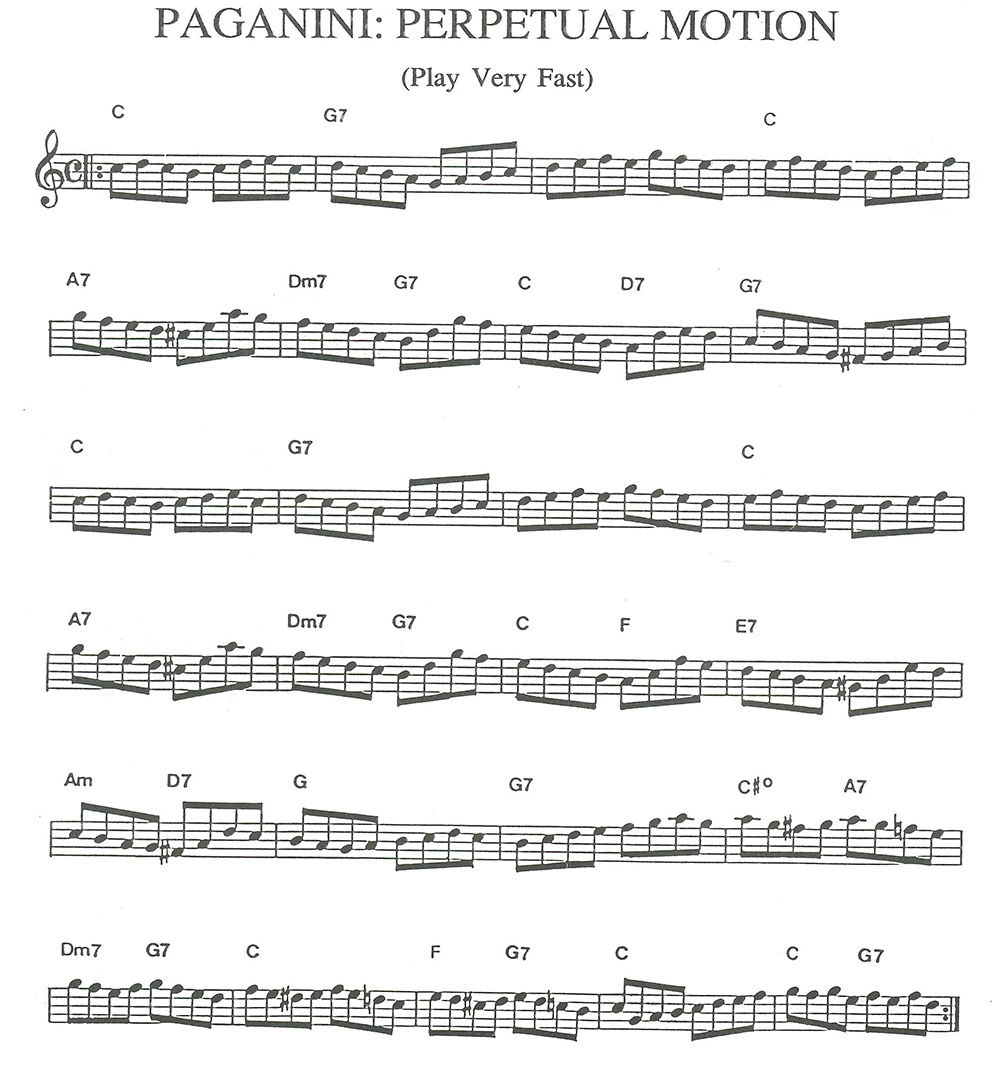

Another example from the violin repertoire, this one by Nicolai Paganini, “the demon fiddler.” Its name: moto perpetuo = perpetual motion (or) melodic continuity.

Lack of space allows us to do little more than set your feet upon this magical path – a path that has taken many improvisers to the top of their craft.

A diligent study of melodic continuity can lead to mastering that “musical mental arithmetic” that controls the creative flow. It builds a sense of intervals, leads to the discovery of guide-tone lines that turn sequences of chords into harmonic progressions, and just might help you acquire that most prized of all musical skills: perfect co-ordination between the brain and fingers!