How To Remember 10,000 Tunes

By Bruce Clarke

Most music has form, and most conventional classical or popular music that uses the diatonic scale or its related modes as its binding agent can be broken down into a small number of acceptable forms. In turn, these forms themselves can be broken down into musical modules of four or eight bar lengths.

Share this:

[feather_share]

The form of the music can be identified the melodic or harmonic repetitions. Within these forms you will hear little fragments, or themes repeated; whole sections may even be repeated.

Repetition, on one or more levels, is a common element in all musics of the world. Its use extends far back into the history of music, and it has been a unifying device in Western Art music, both secular and sacred, from the Middle Ages to the present day.

The overall form or shape is first recognised by determining its length.

You are not doubt all familiar with you are familiar with the many simple riffs, patterns, and bass lines that are associated with it, you can “measure off” each group of twelve bars, as they pass by you during a musical performance.

So there’s a start – you know the twelve bar form and before very long you will be able to recognise sixteen bar forms, twenty-four bar forms, thirty-two, thirty-six and forty-eight bar forms, plus many others.

Imagine you are standing before a giant display case containing the hundreds of thousands of tunes that have passed before the public in the last fifty years.

Tunes that the average professional musician is constantly called upon to perform at the many functions that support live music. Tunes that because they have become standard material are now often recreated directly from the talented musician’s head without the aid of printed music.

Of course, thousands of these tunes were written long before the current crop of young musicians developed an interest in music, or indeed, even before they were born; so when playing these tunes the new player is placed in a strange position. He will be quite often playing these compositions to older audiences that know them better than he does.

Of course, one could argue that providing the player has a large enough supply of sheet music he can cope with any situation that arises. But, unless the player knows how to “look beneath the surface” of that sheet music, and discover each one’s unique qualities, chances are that he will simply skim superficially through the chord symbols and scales to produce another instantly forgettable performance.

But, at the truly creative end of contemporary music, superficial performances of any kind are simply not good enough and a career-minded musician cannot afford to waste opportunities that might allow him to gain a deeper understanding of his craft. With each performance he must move a little further artistically into the innards of the music itself.

How would you cope with the following situation if it happened to you?

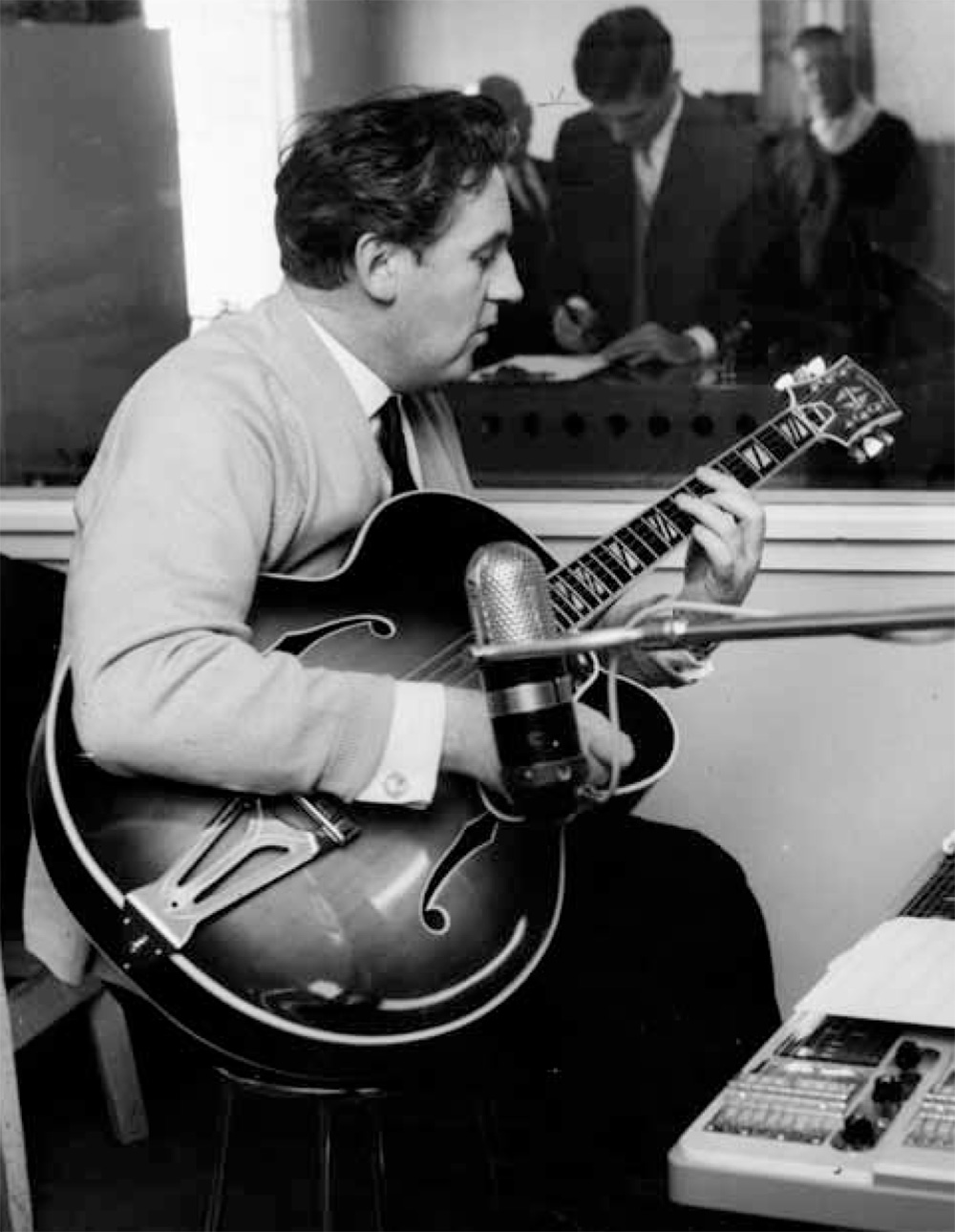

A guitarist joins a name jazz group and learns the chords of the pieces they play. It’s his first break into jazz and tonight the group is booked to play before an audience of jazz enthusiasts. The first tune to be played was written in 1937 and he feels secure in his role as an interpreter of standard jazz pieces. He intends to make it big by throwing in a few flashy scales or modes, run across the chords, give a little grimace here and there and then go out in a blaze of thunderous applause. After all, who’s going to remember much about a tune that was written in 1937?

Even though he is not familiar with the melody or the subtle relationships that co-exist between the melody and the harmonic background of the arrangement, and even though he is not familiar with the many fine performances that have accumulated through the years to make this tune a jazz classic, his confidence is riding high, until the leader steps up to the microphone to announce the song which he does in a strange way. Instead of calling the title, he quotes an obscure line from the lyric, and to our hero’s amazement, there is instant audience reaction they know it. He doesn’t.

You can hear a good example of this on the Chet Baker – Gerry Mulligan, Carnegie Hall 1976 Concerts. Baker announced My Funny Valentine by calling …”Don’t change a hair for me, not if you care for me”

Sometimes you will be playing to audiences that know the music better than you do – audiences that are familiar with the lyrics, the melody and its history of great past memorable performances.

It is your responsibility as a creative musician to put yourself in a superior position, after all, you are the one they are paying to see. If the audience knows it better than you do, you should be paying to listen to them!

Many young musicians that make the move from rock or classical to jazz too quickly, are faced with this problem and it places them in an unenviable situation, where reputations crumble quickly. Don’t let it happen to you. Study form and content, and learn to look below the surface of the song.

How do you get started?

Well, first of all realize that you can not possibly understand, categorize, analyze and compare songs on their form and content until after you come to know a great number of them. “To Know” means to be able to play and sing the melody line, sing (and understand) the lyrics and play and recite the chord changes from memory.

Secondly, you’ll need to take your head out of those Van Halen and Stevie Ray Vaughan songs and work on the standards we call evergreens -instrumentals without lyrics can come later.

Study the work of the great singers, jazz and otherwise: Frank Sinatra, Mel Torme, Joe Williams, Jimmy Rushing, Fred Astaire (don ‘ t forget that some fifty of the best tunes were actually written for him to perform), Ella Fitzgerald, Billy Holiday, Carmen McCrae, Betty Carter, Helen Merrill, Shirley Horn and the others who have applied the artistry to the melodies of Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, George Gershwin, Duke Ellington, Harold Arlen, Harry Warren, Vincent Yarmans, Vernon Duke, Irving Berlin, Johnny Mercer, Hoagy Carmichael, Rodgers and Hart and the great craftsmen who made it all possible.