Bruce Clarke in Conversation

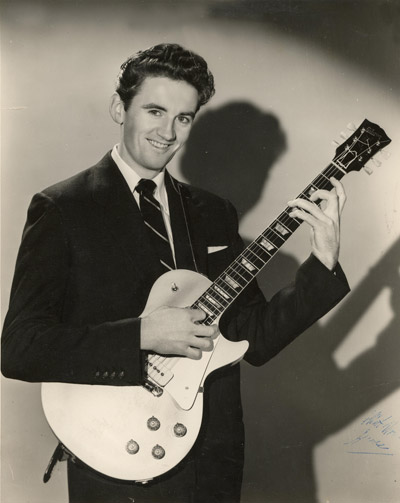

Bruce Clarke has been at the forefront of the Australian guitar and contemporary music scenes since 1949, working as a free-lance guitarist/arranger among many orchestras on live radio shows, and backing overseas artists on concert tours in the dance halls and ballrooms which were popular at the time.

Share this:

[feather_share]

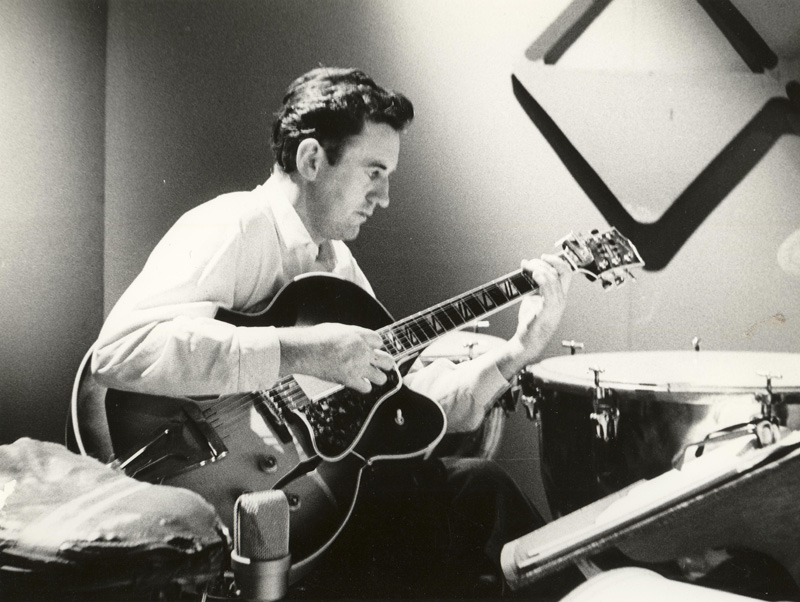

When television brought this era to a close, he moved into film and television music production and composition. He was President of the International Society of Contemporary Music (Vic.), and realised the first major Australian electronic work for the 1968 Adelaide Arts Festival, conducting many first Melbourne performances of the works of Stockhausen, Berio and Webern, and toured Europe as guitarist with Felix Werder’s Australia Felix Ensemble. He has appeared under the batons of Sir John Barbarolli, Charles Mackerras, John Hopkins and others, and in 1981 he played second guitar to John Williams with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra in Andre Previn’s Concerto for Guitar and Ordrestra. He accepted a position on the Music Board of the Australia Council, becoming Kenneth Myer Music Fellow to the Victorian Institute of Colleges, and in 1977 he instigated the popular Jazz Studies program at the Victorian College of the Arts.

He has played in concert and workshop environments with Joe Pass, Herb Ellis, Barney Kessel, Ted Dunbar, Ike Isaacs and Charlie Byrd, as well as his own jazz guitar ensembles. His output includes Jazz Guitar in Concert (published by Allans Publishing) and a variety of study material and recordings. Between recitals and performances, he directs the highly successful Jazz Guitar and Improvisation Study Programs at his Bruce Clarke Guitar Workshop.

Ron Payne: Congratulations on the new-Iook second edition of your Jazz Studies manual. Since its sub-title says “A Study Manual for All Instruments,” I thought we might look at how it could benefit our readers?

Bruce Clarke: I’m delighted that another crop of musicians can pick up on its no-nonsense explanations of the inner workings of contemporary music. But, I must point out that I did not invent the contents – they’ve been around a long time. I think of them as the bits’ n pieces of a musical construction kit that each creative musician must learn to understand and manipulate to bring original ideas to life – those essential tonal and rhythmic building blocks that support our present system of music. I undertook to place them into a logical ‘easy to understand’ order and design a series of practice procedures and assignments that were appropriate for both the fledgling musician and his teacher. Its ongoing usefulness tells me I succeeded! I’ve lost count of the number of people – mostly strangers – who’ve told me how it brushed away the cobwebs and let the sun shine in upon their once hazy music world.

R.P: The original cover displayed a prominent “Recommended V.I.S.E. Text” logo for the new edition, I notice that’s been omitted?

B.C: The cover has changed but the innards remain the same, and because the name V.I.S.E. is occasionally mentioned in the text along with references to classroom procedures, I think I should explain a little of how it all came into being. Back in the mid-70’s (encouraged by Dr. Phillip Law) I instigated the Jazz Studies program at the Victorian College of the Arts and its successful beginnings seemed to promise a bright future for jazz in higher education. Soon after my involvement with the V .C.A., I took off on a concert tour of Yugoslavia with Australia Felix. My constant companion throughout the trip was Peter Clinch, an old friend and musical cohort from the early years of television. Dr. Peter was now a leading educator and a member of the V.I.S.E. music committee. Peter told me of the committee’s plans to introduce a Jazz Studies program into secondary schools, and God forbid, he suggested I should write the official textbook. I resisted – Pete persisted. For two years we argued back and forth until finally I capitulated. He even had Allans lined up to publish it before I’d put pen to paper. The manual entered the secondary syllabus around 1981, embarrassed a lot of people for a year or two and was pensioned off around 1984. The course promised a lot but delivered very little. Once it moved out of the hands of the committee it was badly managed.

R.P: In what way?

B.C: Well, first of all it took a “theory only” approach without mandatory performance back-up. A formula doomed to failure from the start because all forms of spontaneous music making call for theory and practice to go hand in glove. I would even argue that they should be taught by the same teacher, thereby assuring that the students’ musical intellectual growth is kept perfectly in sync. with his instrumental development. This was not possible within the established system as instrumental students needed every available practice period to prepare their material for A.M.E.B. exams, etc. It also fell apart when funds for a proposed “in-service” teacher training scheme failed to eventuate and students were placed into the hands of classically trained, disinterested tutors. Old world attitudes and training methods carry very little weight out here among the computers. Lets be sensible, surely a course in Chinese would employ teachers who could speak that language. Yet, here was an important area of 20th century music assigned to teachers who would rather not know about it. Teachers whose minds, ears and interests were (more often than not) firmly locked into 18th century practices and procedures. It really wasn’t the teachers’ fault; the blame lies with those who mismanaged the whole project. But, thankfully, there was life after musical death and the book went on to bigger and better things both here and in the States. I should mention it received a wonderful review in the American Journal of “The National Association of Jazz Educators.” No doubt that helped it on both sides of the Pacific. Hallelujah!

R.P: In the text you seem to place a heavy emphasis on the word creative whenever you mention moderm music. Isn’t all music creative?

B.C: In recent times the mass-media and the music merchandisers have brainwashed us all into pigeonholing things. Music comes in little boxes labelled Mainstream, Bebop, Classical, Romantic, Golden Oldies, Baroque Schlock and Barrel – the list is endless. Duke Ellington insisted there were only two types – good and bad. Neither is better than the other; I simply use those names to point up their differences. Classical guitar music is a good example of the musicians’ re-creative role, while the higher forms of jazz demonstrate the opposite.

R.P: Do you really believe that all players can share in these ideas?

B.C: Why should a chosen few have all the fun? I’ll admit that a good professional would be severely handicapped without them, but regardless of a person’s musical status, be it professional performer, teacher or student, none can enjoy a full musical experience without some control over both areas. To me, re-creative music starts at the fingertips, while the creative art is a product of the imagination. At the moment of conception all quality music is creative music but one it moves beyond that moment, it passes into the other basket.

R.P: Do you hold to these ideas all the time?

B.C: Of course I do! They’re too effective to be treated lightly.

R.P: How do they affect your students?

BC: It varies from person to person. The important thing with my students is that once they reach a certain point in their development, they have the opportunity and the experience to evaluate the available options for themselves. Some will decide to emphasise the re-creative side of things, others go for the alternative. Some extremely talented players might pick up the challenge of both. But, whatever it is they make the choice. Of course, if we think they’ve made a mistake, we’ll get in on the act as advisors.

R.P: What percentage of your students are career-minded?

B.C: I have five associate teachers who prepare the ground for me to plant the seeds. They take students through the first year or so, building speed reading and correct physical technique – then collectively we decide who is best suited to move up for that jump off the deep end. I give about forty one hour lessons a week and some twenty five of those are hoping to make it a career. Of course, musical skills are not the only things they need – personality, attitude, the ability to work in front of people and to cope with the pressure of high level music making – all come into it. Our workshop and concert programs allow us to find if these qualities are present or worth developing. Past students have had the thrill of playing alongside Joe Pass, Charlie Byrd, Ike Isaacs, George Golla, Ed Bickert, Barney Kessel, Herb Ellis and many other top flight artists. These are very practical experiences because once they leave the safety of our nest, they’ll have to compete with the best to hold down a job. The others, the balance of my students are the lucky ones, playing simply for the joy of it all. They use Jazz Studies I and II plus my guitar teaching manuals to heighten their powers of self-expression. Their main aim is to fully explore and enjoy all that our craft has to offer.

R.P: Your list of clinicians was devoid of classically trained guitarists. Do you have one on your staff?

B.C: No!

R.P: Why not?

B.C: They have nothing to offer us! I trust you will have a lot of blog space because once I get started on the world of the classically trained guitarist, a whole flood of irate readers will leap off their footstools and go for my jugular. Let me qualify my observation by pointing out that for some 25 years the nylon strung box was part of my day to day professional life, so I am speaking from a vantage point that few have occupied. Outside of Julian Bream (whose work I greatly admire), John Williams and a small number of international concert artists who function at the highest level, the classically trained guitarist’s underlying musicianship always worries me. Now, before we get too far into this, remember that I said “classically trained,” and also note that I exclude the many fine players who have extended the newer styles of music associated with the instrument by either avoiding, or rising above, the general restrictive isolated background. So, what could they offer us? Speed reading skills? New insight in modern music? Will they enrich our harmonic awareness? Could they write arrangements for ensemble workshops? Believe me, I’m not being pompous, just practical.

R.P: Is the problem one of finger-style vs. plectrum technique?

B.C: To some extent. The materials and opportunities available to the talented plectrum player are more likely to produce a thinking musician. I’ve met and played with many great jazz musicians who play both styles – Joe Pass, Don Andrews, George Golla, Charlie Byrd, Ike Isaacs and I know of a few others – George Van Eps and Bucky Pizzarelli – but each of these came to the music from a plectrum style background before moving their mastery (of that musical construction kit I mentioned earlier) over to a finger-style approach. The very existence of their recorded, written and playing achievements far outweighs anything the other team have produced in the field of creative music. I find it interesting that Julian Breams rates Django Reinhardt along with Segovia and John Williams and places Joe Pass up their in the same league. I cannot think of one influential improviser who started out from a finger-style base -maybe an early exposure to Jazz Studies I could turn the tables.

R.P: In retrospect how do you view Segovia’s achievements?

B.C: The whole picture of modern guitar begins with him! History books and printed music tell us there were other fine players before him, but we cannot hear them at first hand. We can only draw our approximation of how they might have sounded from the printed page. Thanks to Segovia’s arrival on the scene coinciding with the beginnings of radio and recording, he becomes our first retrievable historical figure. Those early pre-war recordings and concerts gave a dignity to the instrument that still rubs off on all who keep the spark alight. He brought a large part of the repertoire into being, he created the audience – to most outsiders he created the instrument. This heightened interest in the guitar and a growing awareness of its potential in other areas hastened the acceptance of jazz guitar and Eddy Lang along with Django stepped in to set the ball rolling.

R.P: Latter day authorities have cast a jaundiced eye on some aspects of his Bach and early music interpretations.

B.C: They are probably quite right in doing so. After all, each generation should work at refining what went before providing, of course, nothing is lost in the process. It is generally acknowledged that Schnabel’s recorded Beethoven is flawed, but like Segovia’s early work, it weaves a spell that few others have matched. It’s okay for academics to get uptight about such matters; they have to do something to justify their tenure. Do you really believe that old Johann Sebastian would have cared? I think he would have given his left testicle to hear Andres pulverize his preludes. He always came through to me as a good natured fellow! Was there another guitarist around who could have stepped into the breach and successfully carried out the task that Segovia set himself? I don’t think so! So, warts and all I love him! But, I hasten to add that was an a long time ago. Back then the music was fresh and new; this is no longer the case. It’s lost its interest due to over-exposure. Too many players, too little great music. Something new needs to be added, not just more of the same thing.

R.P: Let’s talk some more on these problems you say are confronting the classic guitar today.

B.C: The instrument itself does not have problems (as long as it’s in a playable condition) – the people who play, teach and study it have the problems. A guitar is nothing more than a musical tool, a piece of equipment (comparable to a keyboard or a set of spanners) that a craftsman manipulates to perform a task. If the tools are right any problems can only lie with the craftman’s ability to do the job, or the value of the job he is doing.

R.P: Would you like to elaborate on this?

B.C: I don’t know if I have all the answers – I do have some. I think they are too far reaching to be tossed off lightly in our few minutes. Perhaps we would pick that subject up and cover it in-depth at a later date.

A shortlist of Bruce Clarke’s students might include:-

- Barry Morton: Director of Jazz Guitar Studies at the Queensland Conservatorium.

- Dale Kohry: Ex television, A.B.C., studio musician, now a leading teacher.

- Vince Hopkins: Guitarist with “In the Pocket” and Associate Teacher at Guitar Workshop.

- Pierre Jaquinot: Working musician, Group Leader and Associate Teacher at Guitar Workshop.

- Mark CaIly: Working musician, Group Leader and Associate Teacher at Guitar Workshop.

- Stephen McKenna: Sydney studio musician, soloist and clinician.

- Doug de Vries: Guitarist with Vince Jones Group.

- Simon Binks: Founder of Australian Crawl.

- Andrew Pendleburg: Sports and many other groups.

- Robert Goodge: I’m Talkin’.

- Matt Sandford: Priscilla’s Nightmare and other groups.