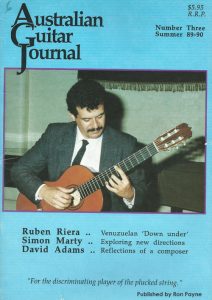

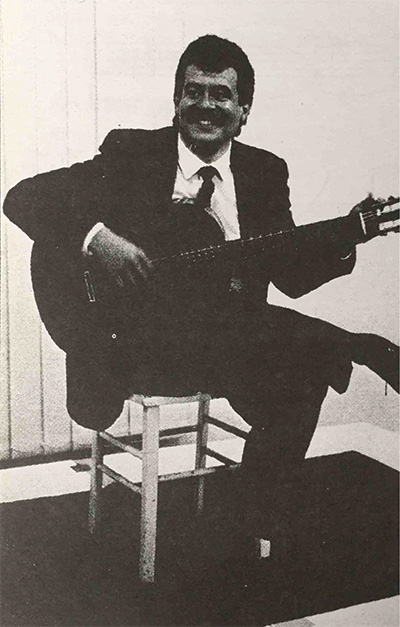

Ruben Riera

By Richard Charlton

Ruben Riera is Venezuela’s leading classical guitarist and was making his third visit to Australia when this interview took place. Ruben had just completed his last engagement in Australia (masterclasses and a recital at Montsalvat in Melbourne) when we had to make an unscheduled stop on the way back to Sydney. While he was tucking into a “steak sandwich with the lot,” I took the opportunity of asking him a few questions.

Photos: Paul Pulati, Hunter Valley Guitar Society

Share this:

[feather_share]

R.C: At what age did you start playing the guitar?

R.R: I was eight years old when I first started and very young (16) when I graduated from the Madrid Conservatorium.

R.C: So you studied in Madrid?

R.R: Yes, I was born and brought up there and then later we moved back to Venezuela. I studied with Antonia Ortega who incidentally was a pupil of Daniel Fortea, one of Tarrega’s students!

R.C: That’s an amazing link. Was music the normal thing to do, given your family background?

R.R: No, it didn’t really influence me. My father was away a lot of the time and my mother definitely didn’t want another musician in the family. She wanted at least one of her sons (me in particular) to have a normal job. I remember when I told my mother that I was going out to pick up my Diploma she said “okay,” and when I brought it home to show her, her reaction was just, “oh that’s nice.”

R.C: You’ve also studied in London?

R.R: Yes, in 1979 I received a grant enabling me to study the lute with Nigel North and also guitar with John Duarte. Actually there were quite a lot of us studying there at that time and it was in the U.K. that I met four out of the seven members of my group Pitangus.

R.C: Tell us a little about this group

R.R: Well, two years ago I convinced my manager Mariam Vava to form Pitangus as a new co- operative of Venezuelan musicians. Its aims are to promote a group of musicians, edit and distribute new music of Venezuelan composers. The group consists of performers and composers; the latter are very much committed to providing special works for the performing members.

R.C: Before you formed Pitangus were you mainly playing solos?

R.R: Mostly, but I had been working with my sister Maria who is a singer and of course duets with my father. We used to perform Sor studies on two guitars. I would play the actual piece and my father would improvise a second guitar part. I don’t think he ever wrote his part down but it sounded the same, most times, and he got quite good at it after a while.

R.C: Getting back to Pitangus and Venezuelan composers, you are performing two new works on this tour.

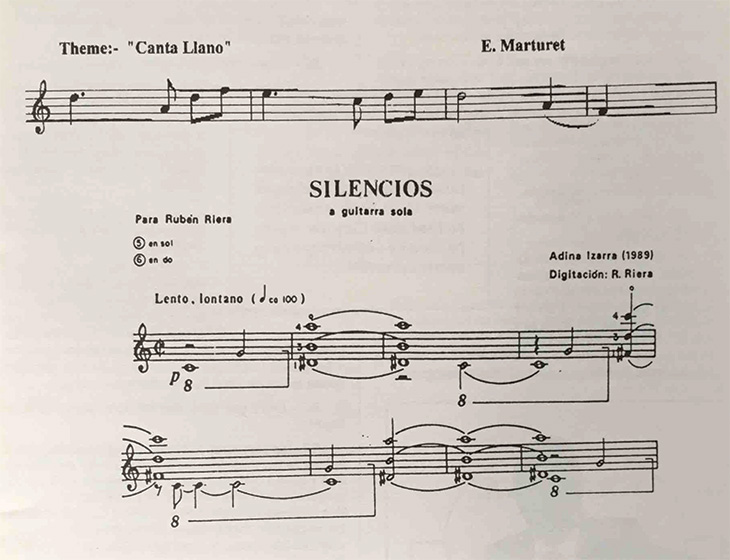

R.R: Yes, Canto Llano by Eduardo Marturet, for guitar and taped delay. It’s a very approachable work and actually his first for guitar- he is presently working on a new piece for me. The other work is Silencios by Adina Izarra. The latter was described by one enthusiastic listener in Melbourne as the best piece since Britten’s Nocturnal!

R.C: These two works are very different in style from each other and different again from, say, your father’s works; do they sum up the trends in composition in Venezuela?

R.R: Not completely, we still have a strong avant-garde movement in electronic and computer music. Adina has her own group that works with keyboards etc. My group mainly plays more conservative 20th century music. I’ve always wanted audiences to enjoy contemporary music and to see the guitar in a more ensemble role.

R.C: So is there a Venezuelan School in composition?

R.R: I don’t think so, it’s really more internationally orientated like everywhere else as in Australia for instance. I do not believe there is such a thing as a school of composition anymore in the world not like when Schoenberg was working for example. Everyone is doing different things now.

R.C: Do you think that’s a general trend?

R.R: I think composers are going after their audiences much more now. In this century composers have advanced much more than their audiences, so that now they are trying to make contemporary music accessible.

R.C: Brouwer recently visited Venezuela, tell us a little about that?

R.R: At the end of August this year he was there to teach masterclasses and lectures about his ideas in music and his dream about the evolution of the guitar for the future. That dream is to see the guitar as a legitimate instrument both in solo and in chamber music, and to expand its repertoire.

R.C: Don’t you think that has been happening since Segovia?

R.C: Don’t you think that has been happening since Segovia?

R.R: In some ways, but guitarists still feel they don’t belong to the mainstream of music, partly because we don’t have a repertoire that can compare with instruments like the violin or piano. The only way to improve this is to push composers to write for the guitar and to try to balance the lightness of the classical repertoire with the 20th century repertoire. This has been one of my goals.

R.C: What’s Brouwer like in his masterclasses?

R.R: He is very approachable and he teaches respect for all types of music. Brouwer was saying that in order to be a good musician a guitarist needs to know not only about classical music but about all kinds of music, especially if your are playing 20th Century music. “How can you play this?” he said, (referring to one of his own pieces) without having ever heard any Chick Corea!

R.C: I’ve noticed your approach in masterclasses is not so much technique but to get people to think about the music itself, the phrasing etc?

R.R: Well, first of all in the masterclass you don’t really have time to change a persons technique unless something is really wrong. You have to just point out problems so that they can work on them with their teacher. I usually talk about phrasing, sound and most importantly the rhythm. I try to make them aware of the different voices in the music, melody versus accompaniment, the bass line etc. Most students play everything as one, I like to get them to bring out certain parts, to hear more of what is in the music.

R.C: This is your third trip to Australia so you obviously enjoy coming here?

R.R: Australia is very similar in character to Venezuela so I don’t feel that I am very far from home and, of course, I have made a lot of friends here. Often I’m asked about the political state in Venezuela and I keep having to repeat that we’ve had a democracy for many years now. Of course we have all the problems of a young country that became rich very quickly but we are working towards the future optimistically. In a small way I feel that by playing Venezuelan music here (such as my father’s, Izarra’s and Marturet’s works) and Australian music (like your piece) in Venezuela, I am helping to breakdown some of the communication barriers between the two countries.