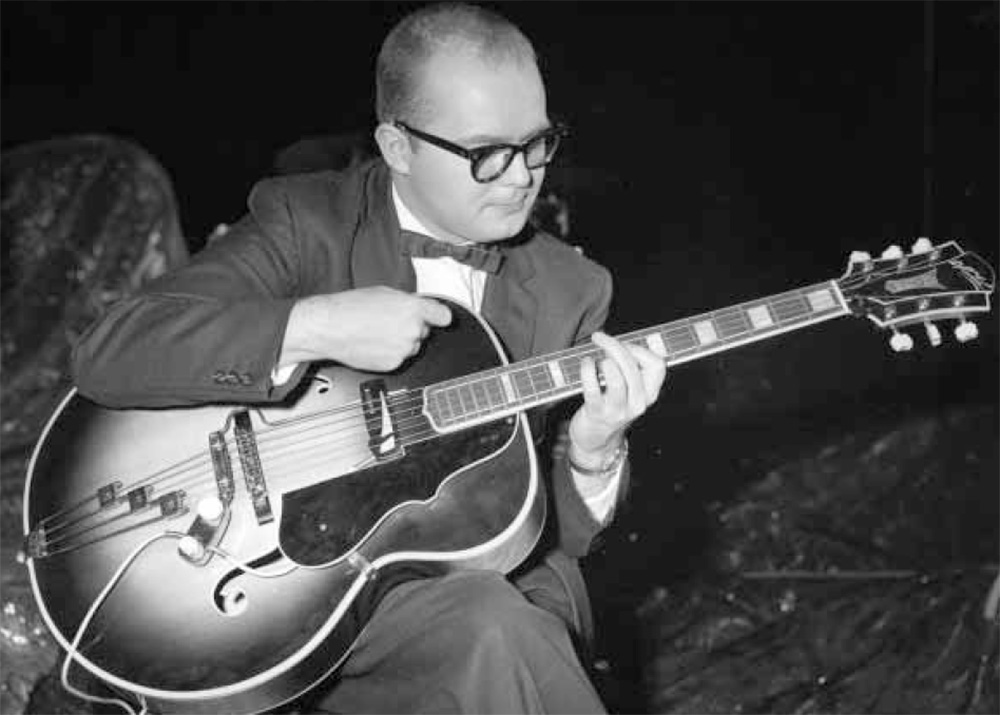

Improvisation and Style

By George Golla

“To improvise: To make up (something, such as music or poetry) on the spur of the moment; sing, recite or speak without preparation.” (The World Book Dictionary)

Share this:

[feather_share]

Were this true in regard to music, our troubles as players of instruments would be over; our problems and tribulations as listeners would be considerable. Imagine a world where no preparation for performance was necessary and listeners were bombarded with ad-hoc rubbish whose only claim to legitimacy was that it was “on the spur of the moment.” The lesson in this is not to take terms like “improvisation” literally. Let me narrow the field somewhat and apply “improvisation” to what I will here describe in general terms as jazz. Since no better word exists to describe this wonderful music, jazz it is.

From the early beginnings, some musicians have felt impelled to embellish a melody, both by overlaying it with compatible (i.e. “good”) notes, and playing “in the cracks” as it were – that is to say, in the natural spaces left between the phrases of the original tune. A fortuitous combination of both factors could, on a good day, provide a respectable melodic performance in its own right – original composition aside. So, here you have in one swoop two events taking place simultaneously. 1) A known melody embellished and perhaps made more interesting. 2) a new, albeit “on the spur of the moment” composition being created. Imagine now only the accompaniment (i.e. rhythm, chords and bass-line) being played, and one or more soloists taking turns to “improvise” over the said accompaniment. Call this “new” tune by some appropriate name or a name relating to the performers’ own experiences, and you have a new genre. To this day, it is common practice to play a tune “straight” with perhaps some thoughtful ruminations by one or more participants, then play it several more times, affording each of the soloists an opportunity to be “unprepared” and “spur-of-the-moment.” Since the tune has to be known and understood, the harmonies remembered and mastered, and a very difficult instrument played without signs of collapse, I consider this to be a high state of preparation, the freedom being in the performers’ right to choose their own disciplines.

As clothing has changed; as motor cars no longer look quite the same; as social habits have been affected by time alone; as musicians now traverse the world in hours, whereas the founders of jazz knew only river boats and trains; as evolution in art has made the early ideas known to young students in a fraction of the time necessary for their development, so jazz and perforce “improvisation” have changed, too. It is quite possible to hear a recording in Australia on a Thursday which was made in New York the previous day. How could this not have an effect on young students, or even on the musicians who made the recording? Granted that good taste, clear and sensible technique and grasp of the material are given, there should be (and there is) a difference in feel, scope and colour between the King Oliver Band (early 1900’s) and Wynton Marsalis (now). Louis Armstrong is still held in high regard more than two decades after his death; Charlie Christian created in a few, short years a new way of playing the guitar in jazz – a way that still has not really been superseded, just enlarged upon. And so it goes. Jazz’s roots, like roots of a tree, are in the past, feeding the here and now.

Stylistically therefore, early jazz had a distinct element of obedience to a melody; a careful, respectful probing of the chords underlying a tune. Seldom (if ever) were flurries of angry notes unleashed, harmonic muscles flexed or entire sections reconstructed harmonically and rhythmically. If there were a small number of highly gifted musicians who could, somehow, anticipate the future developments, they were very conspicuous and are household names to musicians to this very day. Men like Louis Armstrong, Bix Beiderbecke, Eddie Lang and others. Perhaps it is this music’s politeness, its tenderness and innocence, the melody clearly discernible or, at least, within easy reach by the listener, that makes it perennially popular. It makes feet tap, faces smile, shouts of “Yeah” almost a reflex action. It’s a sound of fun, love and relaxation. But, like motoring, it was bound to become more technical, faster, further reaching; more fun for some, less for many. Tempus fugit.

With progress in recording techniques more and more jazz was distributed to the world. The more participants in a game, the more tricks. Inevitably, the “professors” of music made contributions to techniques, harmony began to be understood by more musicians, more precise teamwork was demanded, and a taste for this music once thought of as “naughty” was developed by millions. When the swing era arrived around 1938, an arbitrary division was already created; one not fortunately, endorsed by the musicians themselves. Keep listening!