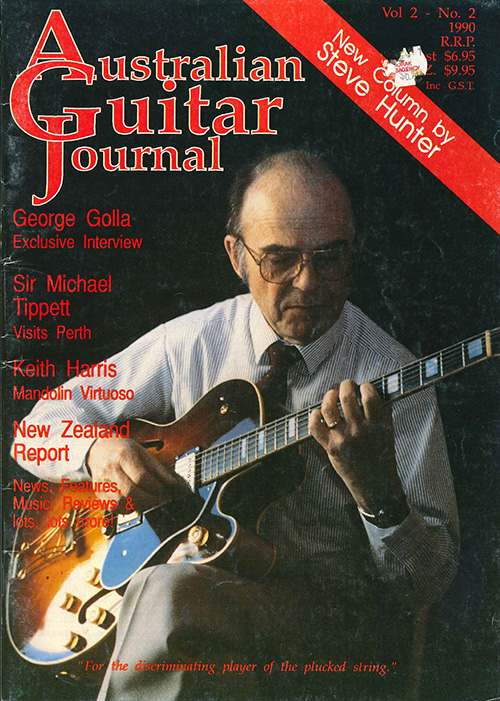

George Golla

In conversation with Guy Strazzullo

Born on May l0th, 1935, George GoIla commenced studying the guitar in 1955 after having played clarinet, saxophone, trumpet and double-bass. His professional life began in 1956 with the advent of television. He subsequently became very active in the recording industry during the late fifties, sixties and seventies.

Readers may remember Eric Jupp’s Magic of Music series – George was to appear regularly in this series for fourteen years. He fondly remembers recording Skippy the Bush Kangaroo during these sessions!

But it was with Don Burrows that George really forged his name. In 1957 he joined Burrows to form a trio with bassist, Ed Gaston. Later, as a quartet they toured the world appearing at various Expo’s and Jazz festivals. In 1973 the NSW Conservatorium employed him as a teacher in the newly commenced jazz-studies program. George’s track record in the recording industry could be considered unmatched amongst Australian guitarists. He has recorded over 100 albums. His total record output with Don Burrows is not really known but could be estimated to be around fifteen albums. As a leader, he has recorded eight albums for Festival, Cherry Pie and ABC Records. The recording he produced on the latter label was awarded “Jazz Album of the Year” at the inaugural A.R.I.A. awards in 1976.

One of his crowning achievements was the Order of Australia in 1985 for services to music.

Share this:

[feather_share]

GUY STRAZZULLO: As a late starter you switched to the guitar after having trained on clarinet and saxophone. How did that come about?

GEORGE GOLLA: In all my teen years and considerably into my twenties I was on a round trip on all the instruments; I liked all the instruments in the orchestra. The only two things that I have never ever wanted to play are the drums and harp – everything else has been considered at some stage. My old man always had a beat-up old guitar around the house, and from the age of five I could always play a couple of chords on it: C, G7th and maybe D and E minor – all 1st position stuff. But it never entered my mind to even consider the instrument seriously; the guitar was not an instrument as far as I was concerned, it was a piece of furniture around the house. So, I wanted to play all kinds of instruments and my favourites were, and probably deep down in my heart still are, the clarinet and the saxophone. So I learnt them, then came to Sydney and went through all the rigours of being told by my friends that, as a professional musician, you would almost certainly wind up in the gutter. Anyway, I came to Sydney, got a room in a boarding house and started playing gigs on clarinet and saxophone. I played in a couple of bands and so forth, but at that time, in that boarding house there lived a couple of guitarists. I had never really seen anybody play the guitar until then; these were modern bebop guitar players.

…If you take a dozen good tunes, they will contain everything you want to know about technique. Everything that I want to know exists in the standard repertoire.

G. S: Anyone that went on to be professionals?

G. G: Semi-professionals. Dave Tatana was one of them; he is a New Zealander who still lives around Sydney – a very nice guitar player. And the other chap Saul Soloman, ended up being an inspector of customs in San Francisco. But these two people actually played the guitar in a way that I had never seen, and it hit me like a ton of bricks. So I took up the guitar and it stuck. I was twenty-one.

G. S: Were you self-taught?

G. G: Yes, I am self taught in everything. I’m a pretty hard guy to teach anything to, I’ve got to learn it. I found the transfer of information to me from other people to be a fairly difficult process without my doing most of the work. I’ve got to find out for myself. So I guess I would be a lousy pupil. I feel sorry for all the people that I teach, of which there have been thousands. I would not like to be a pupil.

G. S: Well anyway, speaking for myself, I think otherwise.

G. G: I’m reflecting in a general sense that the way a lot of teaching is assumed to be done is really just a dream. But it does not work that way; you don’t just keep pouring it in and hope that it will stick. The pupil has to actually suck it in. At twenty-one, I had given away my only means of support. Dave Tatana bought my saxophone; he had played saxophone as well, you see. I said, “well look, I will sell it to you cheaply, provided that I can keep doing gigs on it for a few weeks while I learn the guitar.” I mean how arrogant and stupid can you get? But I then had to go about the business, which I still do to this very day, of playing pieces first then worrying about technical questions after. So I actually taught myself to play a whole lot of pieces; the first piece I ever learned to play on the guitar was Stompin’ at the Savoy. I also believe, quite firmly Guy, that if you know something on a certain instrument (if it’s based on music that will transfer to another instrument without too much trouble) the problem is always in the music ninety percent of music and only ten percent in the instrument.

G. S: Yes you can certainly cut a lot of corners once you’ve learnt an instrument.

G. G: Yes, I already knew what scales were, so it was just a matter of finding out how to play them. I knew which chord sounded good and which didn’t, so by process of elimination I did it. And in those days I had a great deal of energy; I used to practice 12 -14 hours a day. In fact, I was quite a joke in the rooming house you know, “where’s George, will he be in his room?”

From my own experience with teaching classical players at the conservatorium, they have very little, if any, freedom with chords at all.

G. S: So it’s interesting that you actually started by learning a lot of tunes which, by necessity, has lead you into some work right away.

G. G: Well, I was working six weeks after I bought the guitar. My fingers were still soft; after a gig they hurt like crazy. I had to put methylated spirits on them as they hadn’t had time to harden. A gentleman named Gus Merzi had a very good little band, however, the guitar player let him down. I happened to know the clarinet player in the band at the time and he put my name up for consideration. So Gus tried me out, very suspiciously, and I did my first real professional work as a guitarist. I stayed with him for a number of years and worked for several other people at the same time.

G. S: I remember, as your student back in 1981 at the Conservatorium, you used to say a good approach to learning the instrument was to learn a tune and do every thing you can with it. Would you still stand by that view for aspiring young students?

G. G: I still do it for myself. Because if you take a dozen good tunes they will contain everything you want to know about technique. Everything that I want to know exists in the standard repertoire, and provided that I play all the good tunes, which includes Beethoven, Bach and the good rock tunes – and the good Bossa and bebop tunes (most good playable material contains all the ingredients), it’s a better balanced diet than eating hamburgers and swallowing bottles of vitamins to make up for it.

G. S: What about chordal choice? Do you find there is an American as well as Brazilian way of playing Brazilian?

G. S: What about chordal choice? Do you find there is an American as well as Brazilian way of playing Brazilian?

G. G: Neither are classical. From my own experience with teaching classical players at the conservatorium (I teach them some modern guitar too) they have very little, if any, freedom with chords at all. I mean, they read chords and memorise them, but they are not really aware of chord functions, whereas your Bossa Nova musicians are. They are much closer to jazz in the head, than to classical, but the technique is somewhat classical – it’s a hybrid. It’s the two cultures; it’s the African Iberian connection. Jazz and Bebop are the African, North American connection.

G. S: What about people like Waldyr Azevedo the Cavaquinho player? A lot of that music came out of the fifties in Brazil.

G. G: But that’s old Portuguese music.

G. S: There’s also a lot of Bach in that sort of music.

G. G: I heard a lot of Choro while Don and I were there, and that really is very very old. This is why Bossa Nova, which literally means “the new wrinkle,” “the new thing,” changed all that. It came and it went. It’s no longer there, they no longer do it, they’re back to playing Samba – which is what all of it is anyway. Nobody plays that asymmetrical beat on the drums anymore – it has already been and gone. In fact, we had to teach Octavio Burnier (Luis Bonfa’s nephew) Manha de Carnival. He didn’t know it. So it came and went rather quickly, and we were told then by Luis Bonfa (and I believe this to be firmly true), that Australia is the repository for Bossa Nova music. This is the museum where its hiding and kept safe. The Brazilians no longer know it.

G. S: Well I suppose their culture is so closely associated with their music.

G. G: They haven’t got to cringe as they are not afraid. We have found something that works so we are going to hang on to it. Like six o’clock closing.

…Australia is the repository for Bossa Nova music.

G. S: Is that an Australian trait that you find very appealing?

G. G: It is. We are unsure of our own ground and we always need other people’s approval of a music in another country before we say, “Oh yes, it must be good.” We will never come out and make a decision based on our own feelings. I think that’s one of the handful of problems of being an artist in this country.

G. S: Do you think there is some sort of a way for the development of identity?

G. G: Personally I think there is. You’ve got a way you play, I’ve got a way I play, Don Andrews plays in a certain way and any number of younger guitar players have their own kind of thing. But it is entirely modelled on existing overseas forms, my own playing included. I’ve not invented a single technique, nor have I played a single note of music that isn’t a distant and unconscious copy of something I have heard.

G. S: Still, that’s a fairly natural development of things.

G. G: Yes it is. The number of people that have now been doing it in this country for the number of years we have been doing it, we have not overcome it. And this is why the Brazilians have managed to pass through Bossa Nova and go straight on to another phase – it is, after all, theirs and they are not at all self-conscious about it. He giveth and he taketh away, you know. They keep right on going whereas we need some kind of approval, and because Bossa Nova is a music with jazz chords that the public will dance to, we hang on to it. It’s valuable to us. It’s something we can play – like plasma, it fits all blood groups.

G. S: You are saying that Australians live on borrowed culture. Don’t we have our own?

G. G: We have our own, yes. Bossa Nova isn’t ours is it? So how come it’s so popular? It gets you into another argument; one that is fairly fruitless. No matter how long you talk about it, we aren’t going to be able to do much about it. We are not Americans. No matter how much we talk we are not going to become American. So there are things we do naturally that come from a gut level within us of which Jazz, Bebop, Bossa Nova and those things are not components. It’s borrowed culture, it’s sort of sub-tuned. We’ve actually made it our own in a way we think it’s ours. I suppose that’s good enough; I’ve certainly worked on that basis for years.

G. S: You can always establish foundations of course, you never know what can develop from it really.

G. G: I’ve got a feeling that it’s now too late for something totally isolated, anywhere in the world to spring up. We are too connected. I mean, I can literally be in Italy by this time tomorrow. Or, I can switch on the radio and hear something live from New York. I think all these indigenous cultures and ethnic characteristics sprang up and all the people were isolated in little pockets. I don’t think that can happen anymore. Australia’s the last great nation to come along; we came along at a time when that was no longer happening. I can’t think of another nation that within its first twenty or thirty years of existence had air travel. We did. We federated in 1900, in the First World War. There were people flying around in aeroplanes. I think that’s closed the book on having an original style, but this is why I think we will always hang on to things that other people approve of. So if it works in Brazil it’s good, therefore that’s it. I must admit, I play that game to the hilt, it suits me just fine. I happen to like the music anyway.

G. S: There’s nothing wrong with it, as long as it’s beautiful. George, you have obviously developed substantial arranging skills that are very evident in your recordings. You are probably, as far as I know, one of the only guitarists that has done that on record, and been able to orchestrate and arrange music. Did you have the opportunity as a youngster to develop arranging because of the way the scene was set up with the big bands?

G. G: I guess that must have been a component, Guy. I know I have always liked organised sound. I’m not entirely self-taught as an arranger. Somewhere along the line, after some years of already arriving, Russell Garcia taught a few others and myself. For those people who don’t know who he is, he is one of the famous American arrangers who now lives in New Zealand in the Bay of Islands in semi-retirement.

I’ve not invented a single technique nor have I played a single note of music that isn’t a distant and unconcious copy of something I have heard.

G. S: You brought out a book: The Russell Garcia Arranging Book.

G. G: That’s right, there are two books actually. Only one is available here, the better one is not available, strangely enough. Don and I, and a few other people took about half a dozen lessons with Russell. So I’m not entirely self-taught but I’m basically self-educated in arranging; trial and error, you know. Also working things out on the guitar, I think we I are fortunate in the sense that the guitar is an orchestral palette -you can paint sound on it. It’s only a small jump to writing that out for trombones and trumpets and strings. After many many years of studio work I was surrounded by orchestrations day after day. I used to leap across to the conductors’ podium when he was out and have a look at what went on and listen to sounds and compare. So I stole a whole lot of ideas; foraged around and picked up whatever fell out of the sky.

G. S: Research rather than plagiarism?

G. G: Yes, I like that. Jails are full of people who are doing research, I suppose. But that’s how I learnt it. I don’t do a great deal of arranging now, I teach it at the Conservatorium. That actually, physically stops you doing it, because you spend so much time showing other people that you don’t have time to do it yourself. I haven’t ever honestly thought about what you said earlier, but I suppose I am one of the few guitar players that do arrange.

G. S: I’ve never heard of anybody else do it since I’ve been involved in music.

G. G: Yes, it’s usually piano players or trombone players. There was a gentleman in Hollywood, Jack, Marshall, who wrote a lot of television music and movie music; he was a guitarist but is no longer with us. But, you are right, the guitar is the perfect instrument on which to learn arranging.

G. S: You can do closed voicings, open voicings, and along with George Van Eps, you have that orchestral approach which you use a lot in your accompanying. Do you find that the younger generation, with whom you are in touch, being the senior guitar teacher at N.S. W. Conservatorium, research or look into these things? Do you find there’s a willingness to explore harmony and understand its worth?

G. G: You’re asking that because you have a suspicion that it is not so, right? You’re right. Very few are interested in that aspect but there are some and they’re extraordinarily good, but the majority of my pupils want to learn to play solos. If you’re in a certain place in your head with music your playing will reflect that. It’s pretty hard to fool a knowledgeable observer with your level of accomplishment when you play. People sometimes say, “Gee the audition was only 20 minutes, how can you find all this out?” Man, in 20 minutes I can find out 5 times as much as I need about the way you play by just asking you the right sort of questions.

G. S: Can you give an example? Say you have an audition, because there’s a lot of youngsters there, 20-19 year olds, that are very confused about what they’re supposed to know and what they’re not.

G. G: Well the reason for that is very I very simple. Had they listened to the sort of music that we’re going to teach them they wouldn’t be confused. But you have an enormous trans-cultural leap they have to make to get into jazz, when probably they first took up the guitar because it was a tribal totem kind of symbol. The whole thing has to do with being young and with it – in the beginning with a lot of people, right? It just occurred to me what the exact opposite to that is; where the great players come from. It’s first of all a tribal totem then it’s a way, if you’re a bloke, to get chicks because your the lead guitarist – no ones a rhythm guitarist – ever notice that? They’re all lead guitarists. The music they listen to, therefore, does not equip them with freedom of chords. It does not equip them to play lots of different chords in a straight line. Very often they play the same chord rather than the other way. It does not equip them to play quietly so that they can hear other people, and when they do realise that there’s something out there they realise it from a position of having just shot past it. Like, “whoops, that’s why I should have turned off, oh gawd! Now I can’t, I’ve got to go right round one more time.” There are devilish difficulties in that process because by the time you come right round again through your experience cycle a lot of people are really past it in terms of their social freedom. There’s no more time to do that; they’ve got to make a living. They’re married with kids, they get bugged, they find it too hard, or their friends are pulling in other directions. Nearly all the great guitar players in jazz have been hillbillies first: Tal Farlow, Joe Pass, Herb Ellis, Johnny Smith, Howard Roberts, Barney Kessel – all these people, even if they are not physically from the South, they are Southerners in their head. In other words, they’ve sat under a tree and strummed and played. Now pop musicians don’t do that do they? There’s no personal communication.

G. S: That’s beautiful!

G.G: So I think that’s the main difference. Now in my case I was either unlucky or lucky depending, on your point of view. I missed that stage entirely. Good, bad or indifferent, I missed it completely. I had no kids’ guitar period. Never. So the things other guitar players do very well, like some of the nice cowboy things down in the first position, was beyond me. I’ve learnt it since though. I was never an innocent on the guitar, I was always guilty as hell!

I don’t see myself as a jazz guitarist. I play a lot of jazz, but I’m interested in Music.

G.S: What about around your family, did people play music?

G.G: Polish folk music. Dad strummed a few chords on the guitar .But it didn’t really interest me because I wasn’t intrigued with that culture. I was a “yankophile”, I liked the American things – bebop, black jazz and all that. There was a great sympathy and total apathy from both my parents. They didn’t care what I did so long as I was happy; it’s the mid-European parents’ syndrome. I don’t think my father, even now, is quite sure what I do. He knows I play the guitar, but, “Are you alright, what do you do?” So in my grass roots I definitely had sympathetic lack of interference. But no support; they didn’t and don’t know exactly what I do.

G.S: Still, that can be quite good actually.

G.G: I’m glad it happened that way because I could have gone from here to driving an oil tanker, which I literally did for a few years. I ran a day job as a youth in the country. That’s very good, so long as you’re happy. That’s a nice attitude, but our family’s a bit like that. No one’s got any real plans, and to this day I don’t have any real plans. I roll with it.

G.S: I suppose it’s like everything else, you gain such a wealth of experience and the passion settles but the underlying love for the music and the actual instrument is always there.

G.G: The passion doesn’t settle. You don’t just dribble at the mouth any more. It’s like any other favourite pass-time that we all take part in, you just slow up a bit. But the love for the music will always be there and I can now see the guitar as part of the general picture. Although, less than a lot of people, I never was really a guitar freak. I always liked music and I play the guitar, even more so now. I would be quite happy, in all honesty, if I could take part in music outside of the guitar. Either by writing or if somehow I had the gift to play the viola or the ‘cello or bassoon, I would be just as happy, because I realise it’s the music I really dig.

G.S: You have centred your developed technique on the instrument as part of the music you’ve heard rather than the other way around, which is what a lot of youngsters seem to do. Would you agree?

G.G: It’s so easy to tell people where they’re going wrong. I could criticise almost anybody, as I could be criticised by almost anybody, but I think what youngsters aren’t doing is getting a good fix of the right kind of thing to listen to. There are all sorts of reasons, financial, political. I heard a lot more good music during in the first ten or twenty years of my life than young people do now. It’s still possible to do but now you’ve got to dig a lot deeper. The music’s still there, it never gets lost; it’s harder now, you’re just not going to get it on the radio most of the time. You’ve got to spend a lot of money on equipment, discs and tapes. Boy, you’ve got to travel around and spend a fortune in concerts. I got most of mine for nothing. Concerts in the park and good music on the radio. I just realised another thing – neither you nor l have really mentioned the word jazz; we’re talking about music and this is how I see myself. I don’t see myself as a jazz guitarist. I play a lot of jazz but I’m interested in music.

G.S: You’ve always had an inner secret, I suppose, of being a classical guitarist. I’ve seen you at the Sydney Classical Guitar Competition as a judge on the panel.

G.G: You’re not wrong. It’s not much of a secret really. I openly admire them, but it’s not envy. I wouldn’t trade places. I think they’re very blinkered in many ways. I don’t think they’re seeing as much of the picture as they might, due to a couple of fellas who laid it down so heavily over the last 50 or 60 years, that to doubt the word is heresy. And the same thing is happening to them, in many ways, as to the young jazz players. They’re blinkered by other people applying the blinkers to them. Don’t listen to that; don’t do that; that doesn’t exist; that’s not good; that’s not cool. Basically, I suppose I draw spiritually closer to the classical guitarist than the hillbilly.

G.S: So you’re the thinking classical guitarist?

G.G: The lazy man’s classical guitarist. I sort of get all the good vibrations from it, and I have in my life taken it up seriously a few times but I always have to abandon it due to the pressure of work and severe pains in the left hand. (laughs)

G.S: That’s right, you were studying with Jose Luis Gonzales.

G.G: Yes, like most of the other guitarists around town. I had my Ramirez guitar period. And of course going to Brazil revitalised the interest in the nylon string guitar again. But right now, and for some years, I haven’t even owned one. It’s armchair classical guitar I’m afraid. I do love it very much; I think some of the finest music ever written has been written for the classical guitar. In as much as the magnificent pieces, which are short and small, it’s hard to build a magnificent thing which is short and small.

…a very good friend of mine says, ‘you’re never lost if you don’t care where you are.’

G.S: Can you mention some of those pieces?

G.G: I guess it started with people like Sor and Tarrega, and people like that. The music is small, it’s not like a Beethoven piano sonata in length, breadth, scope and tonal contrast. It can’t be, the instrument is small. We’ve made it very big with the amplifier but it’s still small. But nowhere is the musculature that of a strong thing. We’ve just blown it up big. We’re looking at a gnat under a microscope. If you’re prepared to leave it be a nice and small thing, which is basically what the classical guitar repertoire has done, then it’s a superb instrument. That’s what it is, it’s a midget – a beautifully formed one. And the proportions go out of whack when you make it too big.

G.S: John Williams seems to have got it down though. He uses a little bit of amplification in his concerts. It almost seems to be a desperate willingness to re-establish the classical guitar in the world of music. Do you think that’s the way or do you think we need to have a look at some new music? Do you think there’s room for folkloristic influences to come into music like some previous classical composers have done? Maybe even some aboriginal music.

G.G: I think the problem is largely that we’re living in a world that’s several decibels louder than it used to be. Everything is louder. The background noise of a city is louder, trucks and buses make more noise than horse-drawn coaches. If you go to a huge city somewhere in the world, you’ll find the noise is ever-present. There are no quiet places; people are used to hearing things without trying. You no longer go and listen attentively. People don’t say, “Ssh, listen, listen, listen,” anymore. You can hear everything now, it comes at you heavily amplified. If you want to get peoples’ attention, I can see why the likes of John Williams would want to plug into peoples’ expectations more. They need to hear things more loudly. When have you last worked with a bass player that doesn’t have an amp?

G.S: Can’t remember (laughs)

G.G: Well, half my professional career, no bass player used an amp, not even in big bands. Bass players have only amplified themselves about the last 20 years. That means the drummer will immediately play louder, which means the horn players will all want a microphone. What do you do now when the band blows into a new venue?

G.S: Sound-checks.

G.G: Right. Never used to happen! You knew how you sounded.

G.S: It seems to be that dynamics have lost their quality.

G.G: There’s no low at all. In a way it occurs to me that in pop music and the music that is of now, there is no left hand in it, if you’re thinking of music in terms of the piano. It’s all middle and right hand, there’s no movement down the lower end. A definition by some famous composer says that, “Good music is simple in the right hand and sophisticated in the left hand; bad music is the other way around.” You get chords in the left hand, and it’s going like stink in the right hand. Good music will do the other: you’ll have a couple of notes in the right hand and wonderful chordal movements in the other.

G.S: What can students find in a conservatorium? Can they learn to appreciate the overall uniqueness of a good strong note against a chord, as opposed to showers of notes? Not to denigrate fast players of high calibre.

G.G: They can find it there. I’m not saying they will. It’s there, but it’s there outside as well. Not everybody is going to live within travel distance to one of the conservatories for jazz courses to exist. And strangely enough the great guitar players in history haven’t been to those places. The entire jazz faculty up till now at the conservatorium is self taught. I don’t know whether that’s significant, it just might be. If a course gives only answers, it’s only going to coincide with the questions that the students have asked. The rest will end up on the floor. I think it’s a bit like that with information in any field, but certainly in music. The information is always there. You can go and watch half a dozen players. You’ll pick up that which you’re ready to pick up. And the things that predispose you to picking these things up are the real trick, not the course. What the students brings with them in terms of need -not real need, which the teacher can sometimes see long before the student does – but the need that the student realizes that he or she has because that is almost certainly available at these places. But if you don’t put your hand around it and lift it up, you’re not going to walk out with it. I think that is happening a lot. I think we’ve reached a point where education was first a privilege then it became a right, now it’s a bore to a lot of people. And they’ve almost got to rediscover fascination with something. I’ve got some students whose eyes glow during a class. They’re almost drooling with excitement and that’s a talent in itself. They will go further than the person whose got a neuro-muscular system that can play like one of the Gypsy King guitar players do – 908 notes per beat! That’s a different talent; that’s a nervous system that can work that quickly. I can’t do that; I can’t move any part of my body that fast. But there are people that can do that – Allan Holdsworth, John Etheridge – they are so fast that I don’t really know what they’re doing. It goes by me, I can’t hear that quickly. But that’s another branch of the business. The people that can actually say yeh, wow, that really makes me feel warm in the middle; I get goose bumps listening to that chord progression – that, I think is a real gift and a real talent. If you’ve got that you will almost certainly learn to play music.

…I haven’t got into the guitar keys yet when playing ballads in E and A. I still play them in jazzman’s horn keys.

G.S: So guitar pyrotechnics, even by extremely skilled musicians that are musical, is really a different thing altogether isn’t it? It’s debatable whether those people are actually hearing what they are playing or whether it’s a routine in a lot of cases where they springboard to where they do other things during concerts. A lot of it is constructed.

G.G: The pyrotechnics are obtainable in a sporting sense. These people are athletically very able. You get trumpet players who have an extreme high range. The great ones have a higher range than the others. I think greatness on any instrument exists when there’s high technical and emotional ability .But you get some of these people who are about as deep as a piece of paper and who have all the chops under the sun. When I was young they used to impress me, but they don’t impress me anymore – they’re boring, cheap junk.

G. S: Do you think that transcribing is something that should be done at a later stage of one’s musical development rather than earlier?

GG: Well, why is the person transcribing?

G.S: There seems to be a tendency, primarily through the American Education System, to actually transcribe a lot of solos of people to which you may aspire. Transcribing a Jimmy Raney solo, the content can be very sophisticated for a young player that hasn’t had the strong rudiments.

G.G: I’ll make a dreadful confession to you, I’ve never transcribed anything. I’ve transcribed a few things only in my head and sort of played half of someone else’s solo to see if I understood what he was doing, but I’ve never actually sat down and done this. There’s a very high penalty rate for this in arranging. If you write a chart for a big band, the price doubles if you’re lifting something off a record. It’s considered to be that difficult. It doesn’t feel good to me to learn somebody else’s solo.

G.S: That’s interesting. You find that a lot of high class players haven’t done that, Do you think that has contributed to retaining your own personal sound?

G.G: I honestly don’t know, because I’ve never sat down and said I’m going to have my own personal sound. I don’t know whether that’s a desire to protect my privacy, musically. I know I had an incredible fascination with Tal Falow in my late twenties and even then never tried, and I would have almost certainly failed to copy him. I sort of sensed I would never get that right, and even if I did, he’s already done it. I’d lose interest, it’s not mine.

G.S: Really, the spirit of someone’s playing that you like is enough, isn’t it?

G.G: Yes, that’s right. And I can sometimes play in that spirit. I don’t suffer from guitar. I’m not one of those people that has to get all those comers smoothed out; I’m just not a compulsive player I guess. I’m a bit lazy in that respect.

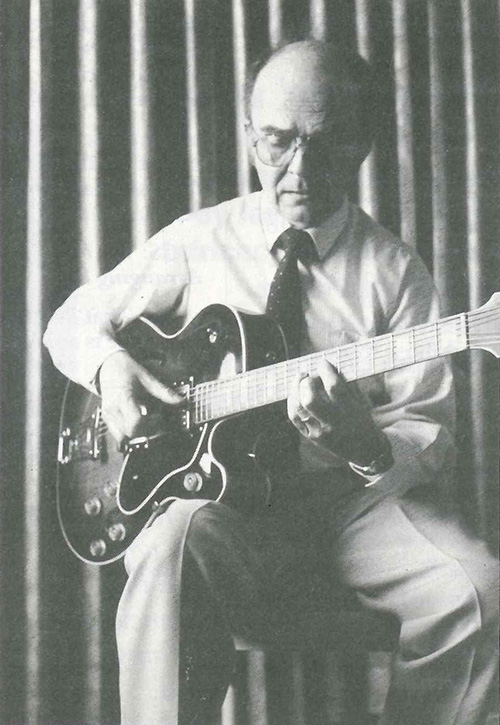

G.S: George, do you want to tell us a little bit about your instrument. Is it a special instrument that Maton has made, or is it standard? Do you have special features on it?

G.G: I don’t, but the one they made for me was the first one of that model.

G.S: The “George Golla” model?

G.G: Right. But it’s now a perfectly standard model, and I’ve had several down the years. And the last two I’ve got are straight off the hook. In other words you or anybody else could have had one just like it. For a couple of years I wasn’t happy with the sound of the active pick-ups so I’ve had a Dimarzio pick-up put in the front unit. I don’t use the back pick-up anyway, so I just left it there and cut the wire. I just didn’t like the sound of the active pick-up; it sounded to me like a note came through the speaker all at once, instead of building up. I like a note that goes “hwa” instead of “ahr.” With the active pick-up the note comes out of the speaker too quickly.

G.S: There’s a growth in it and decay.

G.G: There is. Of my Maton electrics, the older one is around 6 or 7 years old. I love them. I absolutely love them. I’ve not played anything that’s nicer to play. I’ve got a couple of Maton acoustics as well which I use largely for my own pleasure or the occasional recording with a singer. But generally I teach or practise on the acoustic guitars. They’re conventional full scale neck guitars; the strings I use go from 12 to 54 gauge. I don’t like anything much lighter. And I use great big fender plectrums.

I was never innocent on the guitar, I was always as guilty as hell!

G.S: When I heard you play on the Gold Coast a couple of months back I was impressed by the timbral quality right across the instrument. You could hear the same sort of timbre whether you were on the upper register or the lower register, bass or treble, it was very even. Obviously, it’s due to your technique, but the instrument must have something to do with it.

G.G: Not entirely. You can’t get that on a guitar that’s not made that way. You’re always getting rid of the boom down the bottom or the twang on top. I think the stringing has a lot to do with it -the gauge of string. What has a lot to do with it is (a) the guitar itself, and (b) the way I set the amp. Every amp’s different. On my own amps I know how to do that now. I used to set additively, now I set subtractively. I turn everything flat out (all the tone controls) and then I take away what I don’t want; I used to do it the other way. I used to start with nothing and then feed in which means you often stop too soon. Because you often find you don’t need any middle there – you’ve got that just by using a little bit of bass. But if I have everything there then I just remove the edges that hurt. That’s a fairly recent development; I’ve only done that for about a year or so, and it’s definitely improved my sound.

G.S: Would you like to go acoustic?

G.G: Yes, I’d love to if I could get away with it. I think sub-consciously I’ve been after that sound all along on the electric guitar. I’ve made several albums including one with a big orchestra. Also my Duke Ellington album.

G.S: That’s the most recent one isn’t it? It’s been released on the ABC records.

G.G: Don Burrows and I, with various groups, have just made 3 new albums. One of duos from the Quintet, one from the Quintet and one of the Quintet with a large orchestra, and I play quite a few acoustic things on that as well. I would like to play quietly with an unamplified bass, with a quiet drummer and just have a general microphone in front of the band that picks up everything. But it takes courage, because it’s just as odd as when Charlie Christian and those people first tried out those amplifiers and things. Everybody said, “What’s that?” So the same thing’s happening in reverse.

G.S: I think musicians should be aware also that doing that is not necessarily going backwards, it’s more forward. Because like painters, they get so complex in their colours and content during their high periods then as they get a little bit older they start to become more simplistic. They picture life in a sort of clearer way without the problems of having to express themselves.

G.G: All design is like that. Form will follow function to the extent that people might actually make good acoustic guitars again. That’s a lost art. You would probably get a better electric sound out of something made of pressed pulp ply-wood or something, because it’s more inert and would therefore not have the feedback potential. Maybe that will happen again – I privately doubt it. I don’t think there’s any way back from the downward movement. It’s very hard to climb back up from a drop.

G.S: There are some builders in Sydney that have built some considerable instruments.

G.G: Maton have done this for me several times in Melbourne. It’s a minority though. I think you’ve got to live with some of those realities. You can’t wait, you’ve just got to do the best you can. But I think maybe the overall curve will lead that way.

G.S: How do you approach your performances?

G.G: I just play the tunes. I couldn’t tell you how it’s going to come out. There’s nothing planned, and that is deliberate. I’ve planned it that way, because then I’m not going to forget anything.

G.S: There must be some premeditation?

G.G: I guess there always is. Briefly just before the event there’s some control filter you’re using. I guess I repeat some things because I might have played something that was (a) easy and (b) good value on the instrument. For very little effort it sounded good. But I haven’t got into using the guitar keys yet when playing ballads in E and A. I still play them in jazz men’s horn keys. Misty is still in Eb, not in E. I wouldn’t enjoy it if I had to carry around a repertoire, a series of things to remember. A very good friend of mine says, “You’re never lost if you don’t care where you are.” It’s a bit like that.

G.S: How many songs would you know?

G.G: I honestly don’t know. It would be in the thousands. But I honestly don’t know until you say, “Do you know …”, because I forget that I know them. I’m always learning new songs; I just like them. That’s how I practice. I know enough to play several concerts, and so do the people I play with. A couple of the people I play with like Julian Lee, Don Burrows and Ed Gaston really know all the songs I know, and quite a few that I don’t know. It’s by no means unique. It’s bliss because you just say, “Oh, we’ll do such and such in Ab – okay.”

G.S: Like it used to be.

G.G: More or less. They’ve been a lot of new tunes learned since then. It’s a method of operation that used to be. Whilst we’re all reading musicians, we’re ear musicians. I think that’s one thing that is in danger of being lost with jazz.

I think some of the finest music ever written has been for the classical guitar

G.S: What about your writing? You did some duets with Don Andrews a few years ago. Do you feel the incentive to compose?

G.G: I’ve run completely dry the last few years. I haven’t composed anything; I’ve had no desire to. I think it will probably pass. I have periods of great activity, and then have periods of great inactivity. I’m having one of those right now. I’ve had no desire to write anything; I’m enjoying other people’s tunes. I’ve even rediscovered Cole Porter and some of the people I didn’t like all that much 20 or 30 years ago. I thought it was a bit theatrical. Well, I’ve found the next layer of taste under it. There is something else in there and I’m rediscovering a second layer of a lot of those people. I’m not a really good composer, I’m quite aware and honest about that. I can compose something that sounds okay, but l lack the gift of original new melody. That’s a special gift – I don’t have that. My life’s a lot happier if I can play the music of people that have this. Why rediscover the wheel? In my personal life it’s probably been my most active period I’ve ever experienced in every sense. It pays off in everything else. I don’t know how the hell Mozart could write that carefree music when he was dying of uraemia and drinking himself to death. Even Charlie Parker towards the end … and Bill Evans! He recorded some things within days of his death from drugs. And the music is clear and sober! There’s some pretty special people around music. It’s awe-inspiring what some people can put out despite what’s been done to them at the same time. I know a lot of it is self-inflicted, but nevertheless it’s still happening to them. The music reflects some high ideal that they’ve got; they will write a pretty song while the rats are eating them around the ankles. How do they do that?

Hey Guy, What a great interview with a true master. It is so inspiring for the younger generation. Is there anyway I could get in contact with George? as it turns out I have a ‘knoffer club 1958 electric guitar that he owned and sold in 1960 to a young boy. He had been the only owner up until I had purchased it. This guitar feels and sounds amazing and gives me goosebumps. PS it is not for sale. It would be great to have a chat Kind regards, Adam McInnes