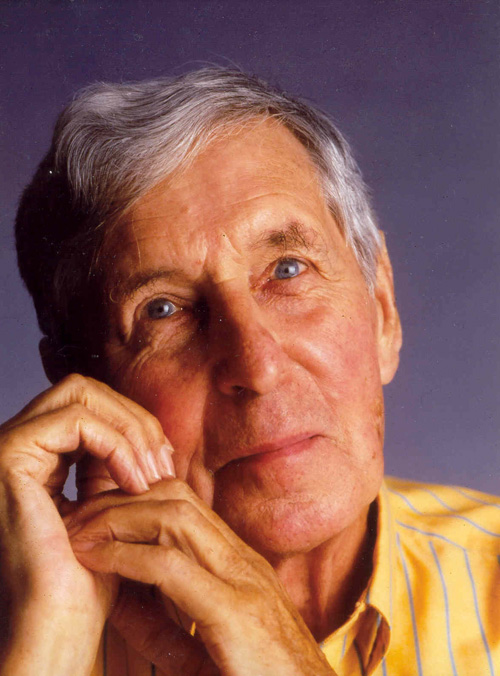

Sir Michael Tippett Composer par Excellence An Appreciation

By Graham Rawlins

Sir Michael Tippett was principal guest of honour during the Festival of Perth this year, and I could do no better than to quote some of the promotional material which says that “…by its growing reputation, the Festival of Perth is now able to attract the very best creators and performers from all over the world.”

Share this:

[feather_share]

Undoubtedly so, for to meet such a man under any circumstances, even in his own country, would be rare. To hear him discuss performances of his own works in person, and then to be able to question him on these same works – impossible!

But here was, and here I was, and with a brief to find out all I could about Sir Michael and his composition, The Blue Guitar . I couldn’t help feeling uneasy already.

I had first discovered the exciting depths of classical music through this man’s work, and knew him to be of greater stature than this small-scale guitar work could suggest, profound and effective though it is.

If only I were to have known the agonies of inner conflict which lay before me, if only I could have seen the pain ….

We were in the Callaway Music Auditorium on the campus of the University of Western Australia, awaiting performances of the Piano Sonata No.2, The Blue Guitar and finally the Songs for Archilles. The audience appeared to be mainly of pension age and I wondered where all the musicians who should have been here had gone instead. Did they not need to know what this man had to say?

The composer entered and was met by cheerful applause.

He took his place alongside the performers on stage for a brief series of publicity photographs.

An instant before the shutter began its work, the face of Sir Michael became a picture of photogenic dignity, presenting the perfect portrait, relaxing to his natural friendly self at the conclusion of each frame – for this man it was just another day in the limelight.

As if by the way of contrast (and no doubt contemplating that definitive performance they were hoping to produce), each of the three young performers twitched nervous smiles at the camera, visibly ill at ease.

So at least the master class could begin: this supposedly frail old man setting himself the task of reducing some of that nervous tension present. He did so by candidly expressing his own attitudes and expectations.

This could not be a master class at all, he told us. A master class was where a performer received instruction as to how to use his fingers, how to go through (and by implication improve) the actions of playing in order to get the desired results.

Being no more than an indifferent pianist himself, he confessed, he could not possibly “instruct fingers” in this way. “I wouldn’t dream of it, because I cannot do it,” he said.

A composer is “inventing” he told us, “even though he cannot do the act of performance (himself).

With this kind of humble honesty, Sir Michael quickly broke down the barriers of formality; the now felt comfortable in his presence and the performers a great deal less stressed.

“Music is at its best when it is performed live, as now,” he continued.

And turning to his work, “A score can never be more than advice for the performer, and I do not feel so strongly as to suggest (that I am looking for) the one answer from all performers.”

Furthermore, “As a player presents the music, it becomes his own (personal) performance, and no one performance can be total.”

For Mark Cloughlan, who had by now taken his place at the piano to begin the composer’s Sonata No. 2, this just had to be good news.

He lifted his hands to the keys.

“Wait a moment please,” said the polite and unassuming voice of Sir Michael. “What is this Sonata about?”

Confusion clouded the pianists’ face. “About?? About? You could see his mind clamoring desperately for appropriate words. At the very moment that he had begun top feel safe and comfortable in the composer’s presence, Mark had been hit by a question so profound it was positively confrontational.

The audience sniggered.

“Yes. What sort of sonata is this?” probed Sir Michael again.

At last, the viewpoint of the composer began to emerge, and he wanted simply to be understood.

In brief, this was not a continuous composition to which the word “developing” could be applied, and the composer felt strongly enough to suggest that such an attitude towards this work would be “dangerous”.

Instead, the player needed to “characterize and contrast quickly” the various elements that were presented in juxtaposition.

“Brilliant!” exclaimed Sir Michael, as he received this answer.

His delight was no surprise and brought a great deal of laughter from the audience, as, by this time, so much prompting had gone on that it was difficult to believe anything more than a single word had originated from Mark himself.

“These characterizations are difficult, considerably difficult because it is one quite short thing to another.

“This is not Beethoven.

“It is put together, not developed, and there are no transitions – the development of the classical sonata is no longer there.”

Even the silences were important, “Short enough to be reasonable,” he said.

The opening chord claims the attention of the listener, like a Beethoven symphony, or even the “Hark!” used at the beginning of a madrigal and as for the end, “I don’t know why the end is there,” he said enigmatically.

So at last we could see the imaginative mind of this great man at work, everything in its place to elicit a response from the listener and no detail to be overlooked, yet even this extensive introduction was overlooked, yet even this extensive introduction was not quite complete.

He now turned his attention once again to the performer and assured him that as a composer he was not here to be critical but to be “…helpful if I can, to make my work understandable to everyone here.”

Without a note having been sounded he had already achieved just that. When most people of Sir Michael’s age were expected to be nibbling biscuits in the day room of the “Twilight Home for the Aged,” here he was positively afire with creative energy as he spoke, animated with such zeal for his work that my own youth appeared dull and jaded.

At much less than half of Sir Michael’s age, it was I who should have been nibbling biscuits.

Mark’s playing was full of confidence and refreshing after such an extended verbal introduction.

At the conclusion of his performance the composer (his high ideals already noted) gave Mark perhaps the finest compliment any composer can give, maintaining that, “Already I have found everything that matters,” and that this is “very rarely done from the (printed) copy.”

Praise, indeed, from a man who gives value to every note, every silence. The analysis could begin.

“Take it away!” laughed Sir Michael as he gestured a grabbing motion at the score. “Better to play to the audience – be extrovert!”

But soon he became more introspective. “This here is Lisztian octaves. I have not invented anything new on the piano at all.”

Moving on, he came to, “This kind of thing which is me” and later still, “This is Stravinsky. I can’t help it,” making it clear that to draw on the technical resources of past composers was acceptable practice, even desirable.

A running arpeggio pattern that had been played admirably enough at first, now took on a far more expressive character under the composer’s guidance.

It was as though “your hands move but you give the idea that they do not,” he said, and at once the arpeggio became lighter, more effective.

To express this idea “absolutely unambiguously” on paper was difficult.

“Yes. How am I to put it down?” he said thoughtfully and laughed out loud again.

Even more dramatic was a compositional device I recognized as used in The Blue Guitar, where a melodic line is suspended over an arpeggiated lower register, accompanied by the written advice “…singing top, ringing below.”

Again, Mark’s performance could not have been faulted in any technical way, but with the encouragement to “make us sit up with all our ears,” he began again.

This was “lyricism of some form” the composer told us, and we must create the “illusion of real singing,” otherwise the “contrast gets a little left behind.”

At this second attempt, the result was so effective it was hard to believe we were listening to the same passage.

“This is a tune being extended” Sir Michael said, “and a composer learns how to do this if he wants to.”

Indeed we heard it – a tune, extended or not, that now took on its own personality, and in some strange way hung in the air like the drifting thoughts of a man.

After one and a half hours we had come to understand this “frail old man” and his music, or at least to recognize some of the things that mattered to him.

What more then could he show us through Craig Ogden and The Blue Guitar? This had been written in collaboration with Julian Bream we were told at first, followed by the typically sensitive touch, a reminder that the guitar was “full of colors.”

It was written after seeing an early Picasso art work of the same title, and was a “translation of that original idea into the form of music, perhaps.”

It was then suggested that Craig play the three sections (Transforming, Dreaming, Juggling) in the order 1-111-1 as the work had originally been conceived in this form. “Julian wanted the virtuoso thing at the end,” he said.

After a very commendable performance the composer stated thoughtfully, “Yes, I think that is what I meant,” which suggested to me that it was not what he meant at all.

Some of the pain I mentioned earlier began to surface. Perhaps the order of the three sections was bothering him.

“I liked it very much,” he continued, “As far as I can tell, a very good, perceptive and sensitive performance.”

Ass far as I can tell…? Oh, the hurt of it all – the guitar did not seem to be doing for Sir Michael what those black and white keys had been able to do.

With an anecdote from Julian Bream that “the guitar likes to murmur and sing to itself,” he continued to address Craig.

“A composer really doesn’t have to work this hard,” he said, impressed by the speed and agility of Craig’s left hand across the fingerboard, continually leaping from one position to another in order to produce the sound.

“I’ve really no idea what you are up to!” he said with a burst of laughter.

“Your ability to do it (produce the music) is fascinating to me.

“Julian will only play this in one hall in London you know – the Wigmore Hall – and as far as the order of performance: 1, 111, 11.

“Yes, that is a performance. I like it that way round.”

After correcting the omission of some slurs in the score, Sir Michael concluded this part of the marathon with the words:

“I really am exhausted by it all.”

Enter Songs for Achilles. Again, a slight twist away from the expected. Forget beautiful singing or sublime guitar accompaniment, it was words that counted here.

Always his own librettist (as far as I know), the composer was most disturbed that a male part was about to be sung by a woman.

“How did you come to this?” he said. “Try to convince me.”

Encouraged to “get something of the poetry of the words over” and “good singing, but more narration,” Lisa Brown did her best.

The character was “a brute experiencing one moment of humility,” he added.

When asked to begin again at a specific point, Sir Michael gave her the cue, “the guitar will give it (the note) to you.” But before Craig’s hands could even think about doing some work, Lisa’s voice rang out with clear, bell-like precision.

It was a masterful touch, the sustained high register note singing out with such authority and confidence as the guitarist sat beside her unemployed, superfluous.

Lisa had proven herself to us beyond doubt as a singer, but a brute she could never be.

Concluding the master class with the words, “I have lived within the music,” we were invited to join our guests in an adjoining room for tea, coffee and biscuits. Aha!

In the corner was seated a strange fellow with a long wisp of ginger hair in the middle of his mainly baldhead.

He was animated by erratic bursts of laughter, relating to the composer how he had been driving along in his car one day with the window open, only to wind it up and trap his own hair between the door and the glass. He sniggered uncontrollably with delight and I concluded to myself that even the rich and famous have to suffer idiots now and then.

At least the man was comfortable in Sir Michael’s presence I suppose, as I blubbered nervously about how I had first come to love music through A Child of Our Time (which amazed him because he had written it even before I was born), and finally got onto the subject of The Blue Guitar.

He shared some of his thoughts:

“Something like that takes such a long time and you have to work with someone…

“Julian (Bream) wanted me to write it so, I said, okay, you teach me.”

But I was looking for something more than this. I was looking for some kind of commitment that Sir Michael might have towards the guitar or, to be more truthful, a few words to confirm my belief that no such thing existed.

“You guitarists are always after music, more music!” he said with exasperation, his normally genteel manner cracking under what had become an entirely inappropriate line of inquiry from me – after having spent three solid hours making it plain to us his lifelong and utter devotion to the great human experience of music, was I seriously suggesting that we needed or could expect something more?

Had I fundamentally misunderstood the man? No, I had not (though it looked as if I had), and as I sat miserably contemplating The Grand Order of Things and what I was doing here anyway, Sir Michael ate his biscuits with a healthy appetite that only a hard day’s work can induce in a man.

Then again, was that my head he was gnawing off?

Next stop would be the Sunday evening concert at the Octagon Theater (still within the University) and a program entitled, “Sir Michael and Friends.”

Waiting for the music to begin, I looked around the full auditorium to see Sir Michael and his entourage in the front row, and a few seats to my left the student or fellow pianist who had been page-turner for Mark Cloughlan during the masterclass.

Mark now walked onto the theater stage to confuse me entirely, the program notes having clearly named Steven Savage as soloist for the night. This was no last minute replacement though, instead I stumbled across a hierarchy of page-turners – the student turned pages for Mark Cloughlan, Mark turned pages for Tonight’s soloist, and as he entered I wondered who Steven Savage would be turning pages for later in the week….

I recognized him instantly of course.

That long wisp of ginger hair in the middle of his mainly baldhead took on a sort of distinguished appearance in this new setting, almost regal you might say.

His performance of Tippett’s Piano Sonatas 1 and 11, and the E flat Sonata of Beethoven Op. 81a were all played well, the Tippett being a particularly sensitive and informed performance.

The Australian String Quartet now captivated us with their international performance standards, producing two early works by Mozart (Quartets K155 and K157) and String Quartets No’s.2 and 4 by Sir Michael.

Could it be that this ensemble of varied strings had more expression, more resonance, more depth of feeling, more dynamic power than our own beloved guitar?

Here I knew was the heart of Sir Michael, the rich textures, the wonderful balance of parts and the sustain – oh the sustain!

He bewitched us, not with comfortable classical formulas, but with an ever-changing web of tension and release, each instrument and part working with and against the other to produce textures of such beauty that at times I feared even my hero Beethoven would sound ugly by comparison.

As I listened, the words of the composer drifted back to me, “Music is at its best when it is performed live, as now…” No recording could capture or reproduce this.

No guitar.

At the last chord and with the lights still dim, the composer stumbled unannounced onto the platform.

He seldom went to concerts now he said, and spent little time listening to performances of his own works or that of the great composers in this way.

Such was the emotional impact of this night that I felt compelled to speak, and shared with us the fact that Mozart had written these two quartets when only nineteen years-old, an awesome thought for this man still composing in his eighty-fifth year, but surely most of all he must have been profoundly moved by the way in which his own works had been played and received,

His closing words have since eluded me, though as he took a final bow he may have said, “Superb music. A superb evening.”

Whatever his choice of superlatives, the emotion in his voice had said it all.

Tippett, Tippett and more Tippett. Was it possible that last night’s concert had lasted for over three hours? Or was it more like four?

The master class on Friday had lasted as long, and here I was like a loony going to meet him again, this time at a lunchtime forum.

I was not showing signs of mental instability and this was not irrational behavior (though my wife was of that opinion), instead, it was because this man had something special, a creative fire you would be hard pressed to meet with twice in one lifetime and I intended to make the most of it. Besides, I had some questions to ask.

You would think, wouldn’t you, that an establishment like this would either have had a sound system that worked or staff on hand capable of making it work.

Apparently they had neither, everyone on stage having a working microphone except the composer himself, and by the time the problem had been overcome, twenty precious minutes had gone by, agony for anyone here during a lunchtime break from work (which was the whole idea of a Lunchtime Forum as far as I understood it.)

The forum did not necessarily improve, the interviewer hiding behind a facade of “informality” and asking uninspired and inane questions about the composer’s childhood.

Already quoted in a newspaper as saying, “You interviewers don’t want to know much do you?” The composer now countered with, “What do you want to know about my childhood for? I think I should start asking you questions about your childhood, I think I’d be rather good at it!”

When a public question time was opened, and after some discussions about opera, I asked Sir Michael about the Octagon Theater concert, more clearly trying to get to the heart of his emotions.

What was it like listening to two of his own works, one quartet written as early as 1942 and the second more than thirty-five years later in 1987?

At last, I had proved my own sensitively, and I knew from the sincerity of his reply that my question had hit the mark.

With great thoughtfulness he explained that he was not a different person in those early years, yet somehow in their performance, the Australian String Quartet had been able to capture the youthful vigor, the exuberance present in his works at that time.

Likewise, they had captured the essence of his later work in quite a remarkable way.

“What about The Blue Guitar?” I asked.

“Yes, I wrote it for Julian.”

Of, course but did the composer like it?

“I couldn’t possibly make such a judgment on my own work. A lot of guitarists seem to like it a great deal.”

I cringe to think that I pressed him still further. I had to know whether there would be any more guitar compositions, and in the end he gave me a comprehensive answer.